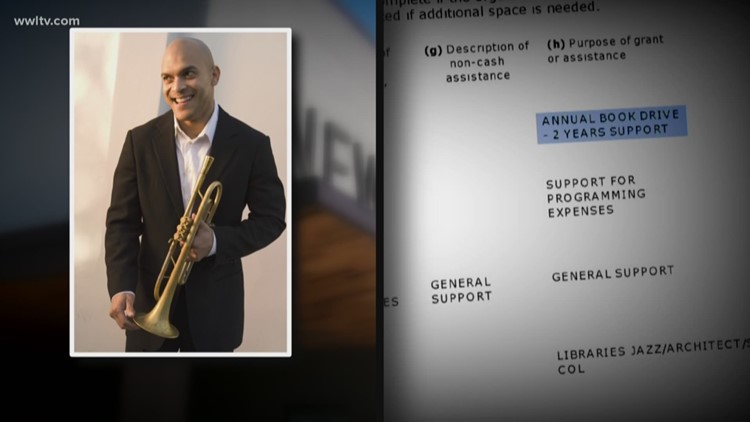

NEW ORLEANS — With a federal conspiracy, fraud and money laundering trial looming in September, Grammy-winning jazz musician Irvin Mayfield and his longtime partner Ronald Markham are trying to make sure a jury never gets to hear audio recordings of Markham that were secretly taped by a state auditor.

In those recordings, Markham answers the auditor’s questions about some of the $1.3 million in public library donations he and Mayfield transferred between 2011 and 2013 from the city’s public library charity to their own jazz orchestra, while each was serving as chairman of the New Orleans Public Library Foundation board and also making six-figure salaries at the New Orleans Jazz Orchestra.

The Louisiana Legislative Auditor launched an investigative audit of the jazz orchestra after an exclusive series of stories by WWL-TV in May 2015 exposed the transfers and a federal grand jury probe.

That grand jury investigation led to a criminal indictment in December 2017, in which federal prosecutors allege Mayfield and Markham used their power at the Library Foundation to funnel donations intended for the city’s public libraries to their jazz orchestra so it could meet expenses and payroll. The indictment alleges Mayfield and Markham moved the money without telling board members and, at times, by lying to them and falsifying board minutes.

In one recording the investigative auditor made Oct. 19, 2017, about two months before Mayfield and Markham were indicted, Markham acknowledges that he and Mayfield never formally informed board members when they would transfer large sums of money from the library charity so their cash-strapped orchestra could make payroll.

“Definitely poorly documented, but it wasn’t as easy as, ‘Hey, man, we need some money, so let’s go run over to the Library Foundation because it’s easy,’” Markham told Louisiana Legislative Auditor investigator Brent McDougall, according to a transcript of the interview filed in federal court.

“Very loosey-goosey board minutes, that I’ve seen so many times. But, no, it wasn’t, ‘Hey, let’s go over there.’ And, again, when you (have a) negative (balance in the jazz orchestra’s bank account), it’s no different than when there is another source of money that comes in because you are negative.”

McDougall asked Markham why there’s no mention of the transfers from the Library Foundation in board minutes until 2013, even though they started in 2011.

“Well, the reason why it came up in 2013 is because we had to start turning over documents,” Mayfield said.

A federal grand jury began sending out subpoenas for documents in 2013, according to court records.

Markham tried to explain to McDougall that they didn’t report the transfers from the Library Foundation because they didn’t report when other jazz orchestra board members gave the orchestra money either. But then Markham acknowledged knowing it was different for him and Mayfield, because they were in charge of both entities.

“There is a big difference, however, between other sources of money that we brought in and this one because we did not sit…I didn’t sit on the Poorman Family Foundation board, right? I don’t have a business with (former Jazz Orchestra board member) Kevin Poorman, so I knew this was a specific situation,” Markham said.

Shortly after McDougall recorded his interviews with Markham in 2016 and 2017, FBI agents asked him for the recordings and some of the financial records he had collected as a part of the state’s investigative audit of the New Orleans Jazz Orchestra.

Markham’s defense attorney, Sara Johnson, argued at a hearing Thursday before U.S. District Judge Jay Zainey that McDougall had coordinated the interviews with the FBI and, therefore, violated Markham’s constitutional rights to privacy and due process by acting as an agent of the federal government without notifying him.

“Markham asked, ‘What are you looking at here?’ and McDougall lies to him” by claiming not to know, Johnson said. She asked Zainey to let her cross examine McDougall and FBI agent Courtney Lantto to show they were working together, essentially to get Markham to meet without a lawyer and say things he wouldn’t have told federal investigators if he knew he was the target of a criminal probe.

But all of McDougall’s interviews came after a series of exclusive reports by WWL-TV, beginning in May 2015, that exposed the transfers from the library charity to the jazz orchestra, as well as Mayfield’s use of money for lavish trips and expensive hotel stays, meals, alcohol and limo rides, as well as for a $15,000 gold-plated trumpet.

Markham had already done an interview with WWL-TV about the allegations of self-dealing, and the station had already reported that a federal grand jury investigation was under way, before the Louisiana Legislative Auditor launched its investigation.

On June 4, 2015, a month after WWL-TV’s first story broke, the Metropolitan Crime Commission requested the investigative audit by the Louisiana Legislative Auditor. The MCC had made a similar request in 2013 that was turned down, court records show. The transcripts also show that McDougall disclosed to Markham the first time they met that his office had received a complaint from the MCC.

But Zainey said McDougall’s conduct – “the secret taping, his four meetings with the government, that’s what bothers me.” The judge gave prosecutors and the defendants 10 days to file further arguments about whether he should hold an evidentiary hearing.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Theodore Carter III said it was “my understanding the government didn’t know” beforehand that McDougall would be recording his interviews with Markham, which is not a typical practice for state auditors.

But Carter argued it wouldn’t have violated Markham’s constitutional right to privacy or due process, either way. Carter argued that Markham was required to speak with the state auditors because he ran the jazz orchestra and it had received public funds, so there was no expectation of privacy.

WWL-TV reached out to the Legislative Auditor's office for comment.

“Considering this is currently in litigation, we decided it’s best not to discuss this until the court concludes what it’s doing,” said Assistant Legislative Auditor Roger Harris, the director of investigative audit.

Carter called the defendants’ desire to interrogate McDougall and the FBI agent about how much they coordinated their efforts “a fishing expedition.”