Brendan McCarthy / Eyewitness News

Email: bmccarthy@wwltv.com | Twitter: @bmccarthyWWL

In a cramped Westbank apartment, five men drink cups of coffee, search for work, send e-mails to the families that drove them here, 9,000 miles on the opposite side of the globe.

These migrant workers came to Louisiana years ago on promises of a better life for their loved ones back home. They longed to feed their families, pay for their children's schooling, maybe one day install plumbing or an air conditioner on their leaking, tin-roofed homes in the Philippines.

Like millions of others, they left the Philippines to find work overseas. These men landed at Grand Isle Shipyard, a regional oilfield maintenance company in Galliano.

But their roofs back home still leak when it rains and their families still can't afford schooling for their children.

Now they say they were lured here by lies, and they are instead treated like slaves. Promised salaries of $20 an hour, when their paychecks arrived they broke down to a mere fraction of that, sometimes little more than $3 an hour.

'They made a lot of promises,' said Ferdinand Garcia. 'They made us believe that everything to be good in the long run. But everything just a promise. They lied.'

These workers point to 18-hour workdays, sometimes up to 400 hours a

month for measly pay. Some say they slept in a retro-fitted storage

container, their passports held by their employer.

A WWL-TV investigation uncovered what appears to be a system of human trafficking, with immigration paperwork allegedly based on lies, and workers holding numerous and fake social security numbers. We found a number of apparent violations, from immigration policies to labor and workplace

standards.

The workers say their conditions were so intolerable that some of them escaped from the company's boardinghouse. One man crawled under a fence, fleeing late at night with the assistance of an American co-worker.

These Filipinos welders, scaffolders, pipefitters came to the United States as skilled workers, but learned quickly that they are at the bottom of the economic food chain. They say their work here included washing the CEO's car, cutting his grass, picking up trash and scraping paint at his restaurant.

The workers said they were threatened with deportation if they complained.

'But they said if they find out I am gonna complain, there will be trouble,' said Eduardo Real. 'We just love our family. That's why, we never eat supper, we just keep going and going to make money.'

Their entry into this country is overseen by two separate countries and multiple federal agencies. Still, they slipped through the cracks. And their presence was mostly unnoticed until November, when some of them died.

On the morning of Nov. 16th, an explosion rocked an oil platform out in the Gulf of Mexico. The fire, on a platform owned by Houston-based Black Elk Energy, killed three Filipino men and critically injured three others. Each of them was subcontracted through Grand Isle Shipyard, which had been contracted by Black Elk.

They had been recruited here through a company with ties to Grand Isle executives.

Hundreds of other Filipinos have worked with Grand Isle in recent years. And shortly after the explosion, we found half a dozen of these former workers living in a run-down, two-bedroom apartment on the West Bank.

They had been subcontracted working at Grand Isle, some just months ago, and are currently part of a class action lawsuit. They made shocking claims about their pay and workload. And had paperwork to back it up.

'Right here, the first time I started working with GIS I got a salary of 1,500 dollars a month,' said Eduardo Real. 'That's a month. We worked 12 hours a day, seven days a week. Just for that whole month, you know. Continuously, on off shore.'

Real's paperwork is like many of his other former colleagues: the numbers are astounding: about $4 an hour.

'So we worked, sometimes in a week, 120 hours. They are only paying us in overtime after 84 hours,' Real said. 'We just only found out somewhere, when the Americans talk to us, 'Why is your salary so small?'

On a rare day off, Real, who has a visa only for offshore work, was pushed to do more.

'They are treating us as slave. I really feel that, especially, our boss, always calling us saying hey, come here, clean our buses, clean our car, do cutting grass to our boss house. Always doing like that...We are not supposed to do that.'

We've sought answers from Grand Isle Shipyard's CEO Mark Pregeant since November. He refused to comment several times.

So we decided to follow the pipeline backwards from the platform to its origin, to the Philippines, where we found a global story of money, power and people.

One of the biggest exports from the Philippines is humans. About 11 percent of the country's 92 million people work overseas.

Labor migration is a way of life for Filipinos and a big business. Overseas workers sent the equivalent of more than $17 billion U.S. dollars back to the Philippines in 2009.That total has increased steadily over the last decade.

And amid this booming business, lurk unscrupulous recruiters, both domestic and foreign, who prey on Filipinos.

The U.S. State Department's own trafficking report notes that a 'significant number' of Filipino men and women are 'subjected to conditions of involuntary servitude worldwide.'

Skilled workers there earn the equivalent of only dollars a day. Meanwhile, permanent jobs are hard to come by.

It's evident at a downtown job market, clogged by thousands of out-of-work men on a recent weekday afternoon.

Recruiters simply hold up placards advertising opportunities, beckoning the men and their

backpacks full of documents and certifications. Meet the requirements? Just sign on the dotted line, and you too can soon join the country's legion's of overseas workers.

Ferdinand Garcia saw a recruitment company's ad in the newspaper.

'When you hearing about America,' he said. 'You just ring the bell. Come in here. I want to come. I want to go there. It is the land of the free, land of the brave, and land of the opportunities.'

Ferdinand's father was a welder and he told his son about overseas work, especially in the United States, a 'greener pasture.'

There is no grass anywhere near the welder's home Bataan, a two-bedroom shack he shared with his wife, their four children and grandchild. The cement-floored house has holes in the roof. The

kitchen is outside, along with four fighting roosters, carrier pigeons, and a mangy dog.

'I only found out when his application was already in,' his wife, Marilou Garcia, said. 'Even then, he was having a difficult time coming home because he didn't have enough money. He barely had enough money for his application.'

Sitting in a plastic chair, in her dusty backyard, Marilou Garcia broke down in tears, talking about her husband's decision to leave.

'I had mixed feelings. I was feeling sad because we are going to be separated, but ok, somehow, because we would have a better future for the family.' That was a long time ago. She hasn't seen him in three years.

Through the recruiter, Garcia worked as a welder at Grand Isle Shipyard.

His optimism faded quickly. He said his paychecks were a mere fraction of what he was supposed to earn.

'Every paycheck, they wouldtold us that it's going to go up, it's going to go in, it's going to get a raise. But it never showed up. They always deduct a lot of things, a lot of money from us.'

He and others say costs for things like room, board, personal protective equipment and tools were deducted from paychecks.

His family struggled.

'I think he reached his boiling point when the two kids got sick. One of them almost died because of dengue fever,' Marilou Garcia said. 'We had to turn to loan sharks.'

Later, they pulled their daughter from school because of the costs. Ferdinand Garcia made the decision, told her so in a long distance phone call.

'And I had to take a deep breath when I told her that: If you could understand me for this time, for this moment, that you have to stop. She just replied like, 'alright, I understand what you are going

through.'

Elsewhere in the Philippines, we found other former Grand Isle workers who shared the same stories, and had similar paperwork to back up their claims. They said they were treated unfairly, their jobs at times unbearable. But it was a job. And their only other option was coming back home to work.

Ellene Sana, of the Center for Migrant Advocacy in the Philippines, said few overseas workers complain. That's because slave-like conditions elsewhere, can still mean more prosperity than what's available at home, she said.

She says that many overseas workers are reluctant to complain about illegal recruitment, pay and working conditions because they earn more there than they can at home.

'In most cases they do not file a complaint to the Embassy because they would rather keep their employment, even if they are working many long hours,' she said.

'Their standards have maybe lowered down. Like, its better that we get something than we come home and get nothing. Because the perception is always like there is nothing here in this country. '

There are also legal questions about the immigration process, how the Filipino workers get here and stay here. Several workers showed us multiple social security numbers they said were provided to them through their employers.

They said they knew they were being exploited. They knew they were cheaper than American workers, their skin color darker than most.

'They can make money with us,' Real told a reporter. 'Let's say they gonna hire you, they gonna pay you $20 an hour. They gonna hire me, just only paying $6 dollar, $10 dollar. So they are gonna make more money.'

Rufino Orlanes, a pipefitter, said he helped the recruitment company with ties to Grand Isle interview and choose Filipino workers. He soured on the company in time.

'It hurts to be discriminated,' he said. 'It hurts because we both persons, you know. We are just the same people in the world, living. But with our color, being discriminated is, it's a little depressing

for us.'

So how do they come to work in Louisiana?

Hans Cacdac, the head of the Philippines Overseas Employment Administration, explained that a licensed Filipino recruiter first links up with an overseas company. The two must receive accreditation and register in the Philippines. Once approved, and with contracts signed, the workers go to the U.S. Embassy for a visa.

The work contract signed by the Filipinos is actually with one of several recruiters, DNR Offshore and Crewing Services or D&R Resources, both of which have links to Grand Isle Shipyard executives.

Cacdac said Grand Isle Shipyard can't be its own recruiting company, that they must remain separate entities.

'That is something we will look into how they are separate,' Cacdac said.

In a statement released late Friday, an attorney for Grand Isle Shipyard, said Grand Isle vehemently denied affiliation with the recruiting companies.

But records from the Louisiana Secretary of State link the two.

An American businessman and two Filipino nationals are behind a web of companies, and WWL-TV followed the paper trail that links a series of recruiting firms with Grand Isle through addresses, founders, even company letterhead.

Filipino national Randolf Malagapo; Filipino national, Danilo Dayao; and Bryan Pregeant, the Vice President of Grand Isle, created a Louisiana company called D&R Resources Inc. in July 2006, records show.

The company used the same address 18838 Hwy 3235, Galliano as Grand Isle Shipyard. Six months later the company's name changed to D&R Offshore Inc. It dissolved in September 2008.

The ties don't end there. These men are behind a web of companies with similar names.

A separate company, D&R Resources LLC, was created in January 2007, on the same day Malagapo and Pregeant's other company changed its name.

Records show D&R Resources, LLC, is an active business. It has three directors: Malagapo, Cutiepie Nilfil R. Peralta, and Danilo Dayao. Its business address is the brick house house on South BayouDrive in Golden Meadow, which is owned by Mark Pregeant, of Grand Isle

Shipyard. Malagapo lives there.

WWL-TV confronted him there in December 2012.

'I'm not supposed to talk to you about it because this is already in the court,' he said. 'So we'll just leave it to the court.'

He repeatedly denied his company is tied to Grand Isle Shipyard, saying they were independent.

Nonetheless, documents obtained by WWL-TV, show he signed Grand Isle Shipyard work certifications. On Grand Isle letterhead, Malagapo is listed as the 'Treasurer/Executive Manager.' And his e-mail address is tied to Grand Isle's website.

We also obtained immigration paperwork which call into question the independent relationship of the companies.

Documents show Grand Isle Shipyard executives were behind yet another company Thunder Enterprises that helped bring Filipino workers here under a specialized visa. The paperwork notes that D&R Resources Inc., is a 50/50 joint venture between two Fiilipino nationals Malagapo and Dayao and a separate company, Thunder Enterprises.

Thunder is a Louisiana corporation established in 1996. Its three directors are Mark Pregeant, the CEO of Grand Isle, and Bryan and Brad Pregeant, its two vice presidents.

The immigration paperwork states that Thunder Enterprises invested $200,000 in D&R Resources Inc. This is in the form of two promissory notes of $100,000 secured by Malagapo's and Dayao's real estate in the Philippines.

Under this set-up, the companies can bring Filipino laborers here under a specialized E-2 investor visa. This visa allows holders to stay longer in the United States than a typical guest worker visa. The visa is also renewed more easily.

The E-2 visa is for people coming to this country to develop and direct a significant business interest and does not apply to ordinary skilled or unskilled workers according to the U.S. State Department.

Several of the workers interviewed showed us their E-2 visas and explained that they weren't sure what the terms meant. We asked Ferdinand Garcia whether he invested in any recruiting company.

'No, they just want us to pretend, I think, to be an investor,' he said. 'They said I'm investing my skill. They just lied to us.'

Garcia claimed that in September 2007, a Grand Isle executive took aside about a dozen of the Filipino workers who had E-2 visas. Garcia said they were told: 'Do well in your job, be good, and then we are going to make your immigrant papers for you, we are going to do everything we can.'

Garcia thought if he worked hard enough, he could one day be a U.S. citizen, maybe bring his family here. Our investigation found more documents related to an additional, more recent recruitment company linked to Grand Isle.

This company, DNR Offshore and Crewing Services employed the workers who died months ago

on the oil platform.

Created in 2008, DNR Offshore and Crewing Services is based in the Philippines and registered with the Philippines Overseas Employment Administration. Records show Cutiepie Nilfil R. Peralta is the head of the company. He is the same man behind D&R Resources LLC.

More than a dozen Filipinos who worked with DNR Offshore Crewing and Services say the company's name represents the initials of the first names of the three men behind it Danilo Dayao, Nilfil Peralta and Randolf Malagapo.

With this information, we again sought to speak with Grand Isle Shipyard's CEO Mark Pregeant.

Late last week, the company's attorney released a statement to WWL-TV. 'GIS looks forward to its day in court when it can defend against these baseless allegations.'

Attorney David Korn said the Filipino workers named in the lawsuit were not 'employed directly by GrandIsle Shipyard.'

Korn noted: Grand Isle Shipyard and D&R Resources 'are separate companies with separate ownership.'

According to him, D&R Resources, LLC is a 'subcontractor to GIS for offshore work on platforms in the Gulf of Mexico' and provides skilled Filipino workers.

Korn also said DNR Offshore and Crewing Services, of the Philippines, 'is not affiliated with Grand Isle Shipyard.'

He added that 'D&R Resources has engaged DNR Offshore and Crewing Services to recruit skilled Filipino workers who want to work on offshore projects in the Gulf of Mexico.'

But again, records appear to contradict these claims.

WWL-TV obtained DNR Offshore and Crewing Service's own company newsletter. It states explicitly, on the first page, under the Grand Isle Shipyard logo, that Grand Isle Shipyard 'was responsible' for creating the business.

Grand Isle's attorney also trumpeted the conditions of the company's bunkhouse, a former bowling alley near the company's headquarters. He highlighted the amenities, such as a game room, exercise room and free wireless internet.

More than six Filipino workers told us this was true,upgrades to the renovated bowling alley were made in recent years. They said changes had been made after years of Filipinos sleeping in cramped, retrofitted storage containers.

And two workers from Batangas said they were forced in their off-days to renovate the bowling alley and upgrade the bunkhouse to house their Filipino colleagues.

We sought months ago to see the facilities. A Grand Isle employee ushered us away from the property.

In the Philippines, news of the Grand Isle Shipyard allegations has spread slowly.

Hans Cacdac, head of the Philippines Overseas Employment Administration, said he watched an earlier WWL-TV report on the internet and was concerned about some of the allegations.

'I think we need to look into it closer here in the Philippines,' he said.'It is our responsibility to investigate. It is our duty to look out for the welfare of our workers.'

Still, no investigation has been opened.

During our interview, Cacdac's staff pulled DNR Offshore and Crewing Services file. There is no record of any complaints.

'We know that on the American side, we are still trying to see if whether there are criminal investigations going on the American side,' Cacdac said. No one from the U.S. government has contacted him.

Ferdinand Garcia says he did call the POEA years ago to complain. 'I used to talk to them back in 2010. December of 2010,' he said. 'I told them about the unsafe acts of GIS and the things that they were doing to us.'

Garcia alleged that the POEA staff suggested he e-mail the recruitment company to voice his complaints.

Days after the Cacdac interview, roughly 30 Philippine human rights activists held a protest outside his office. They shouted 'Down with DNR' and held signs demanding justice.

Cacdac can recommend the Philippine government open a criminal or civil investigation. But his office receives more than 4,500 complaints a year. And he said his office has 16 investigators and an a heavy workload.

Also, the onus isn't solely on his office.

'As we say, management of the process is not just done by the country of origin alone,' Cacdac said. 'Once that worker is in the U.S., then obviously, that worker is under the jurisdiction of U.S. law and the policy. At that point, it is the receiving country, in this case the United States, that now handles the welfare and working conditions, etc, of that migrant worker.'

The U.S. Embassy in Manila is the one that would review the work contracts, immigration paperwork, and applications of the laborers.

The Embassy declined to address this case specifically, but agreed to talk their efforts to combat trafficking.

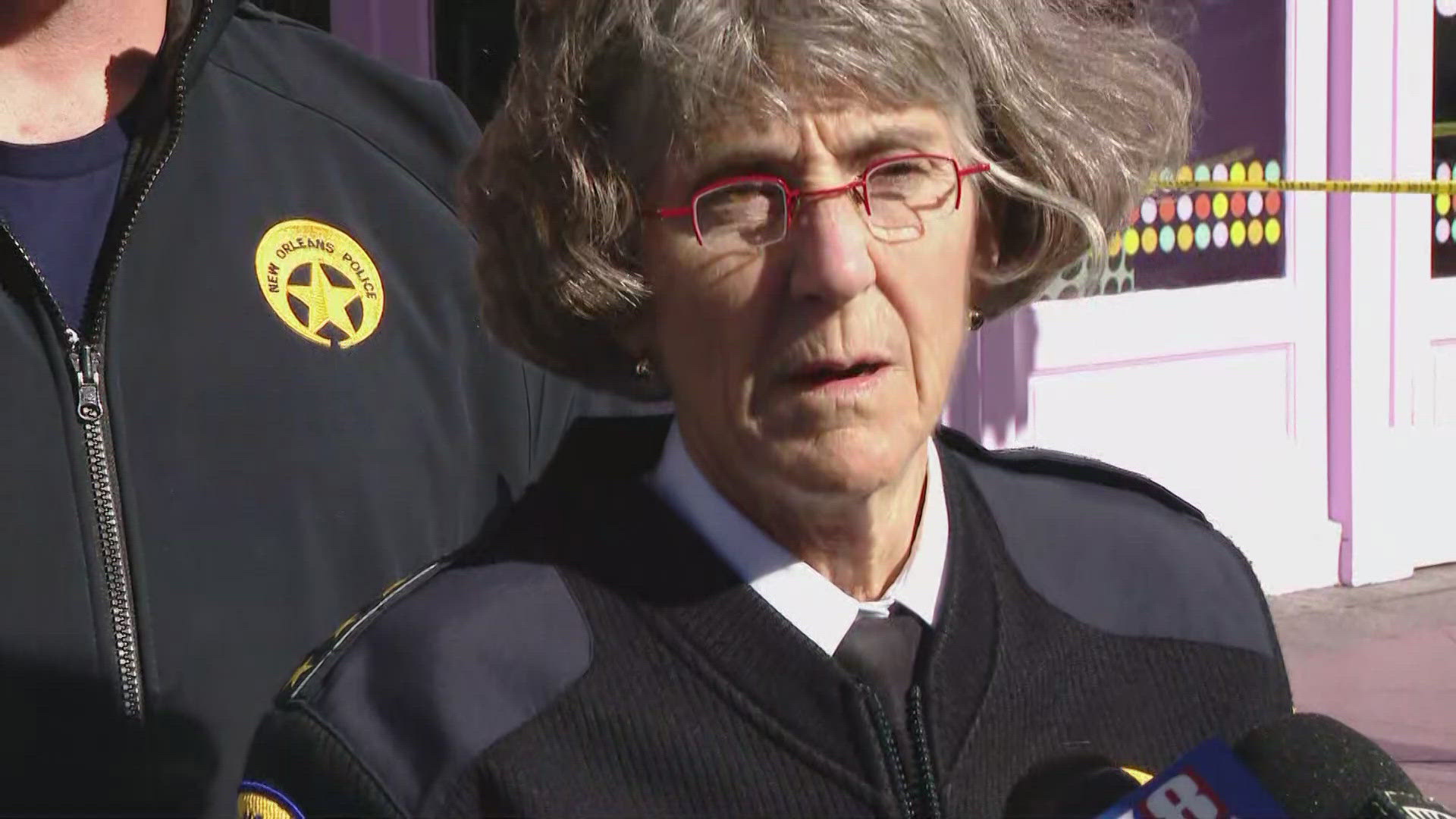

'For the forced labor side of trafficking you have to do a lot more investigation,' said Pam Pontius. 'You have to have a strong labor department, you have to have a strong judicial system, you have to have a worker that is willing to come forward to say that something is not right here.'

Pontius added that the key is getting the message out to trafficking victims.

'And then also helping to provide good protection for the victim's aftercare also, and prosecuting the traffickers also. Because they do have a very strong anti-trafficking law domestically.'

She noted that last year, the Philippines had its first ever criminal convictions for labor trafficking. All of its other previous convictions involved sex trafficking.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security will not say whether there is an investigation into Grand Isle Shipyard. The civil suit is pending, and could take years to resolve.

For now, work continues as normal at the shipyard and out in the oilfields.

From their modest West Bank apartment, among donated goods and items from Catholic Charities, the five former Grand Isle workers bide their time. With their visa clock ticking down, they seek out jobs, whittle away the day and pledge to fight Grand Isle.

'It's a nightmare because, you know, in spite of my age, I should stay with my family in the Philippines,' said Ricardo Ramos. 'Instead I am here fighting for my principles....I don't want to surrender it. I surrender everything - my family, my kids. They are sacrificing. It's been a year right now that we don't see each other. But because of the case, I'll never surrender my principles.'