NEW ORLEANS — Though it was a landmark event, the 1866 Mechanics Institute Massacre was forgotten over the years. The unveiling of a historical marker followed by a public apology by New Orleans City officials is the first acknowledgment of the atrocities committed against Black men who advocated for Black suffrage in the aftermath of the Civil War.

The ceremony took place at the Roosevelt Hotel, the site of the former Mechanics Institute.

Beneath the facade of a luxury hotel, tour guides and historians like Malik Bartholomew can't help but think of the gruesome reality of what happened at that site on July 30, 1866. It was more than a year after the Civil War ended.

“It was a beautiful Greek revival building in this spot where the Roosevelt Hotel now resides,” says Bartholomew. “There would have been people coming mainly from Canal Street. The crowds grew and the friction grew. You have people who are actually on the side of the rally trying to get into the institute for help, for safety and those people are actually shot as they are going inside the building. According to reports, the inside of the mechanics institute was soaked in blood.”

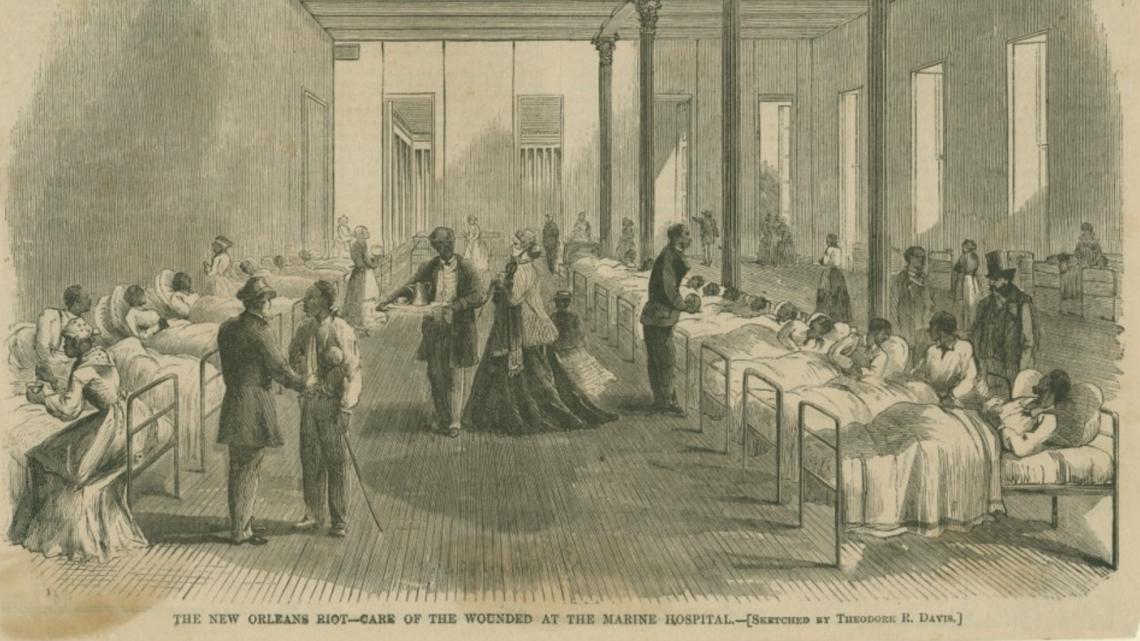

It's reported between 40 and 50 people died that day, mostly Black, while hundreds of Black innocent bystanders were targeted.

In the early stages of the Reconstruction era, laws were passed to give greater freedoms to Black people. Still, they had no voting rights and were under "Code Noir" or Black Code.

“The year prior to the massacre was when the state legislature moved into the Mechanics Institute. So that was the reason that the convention met there,” says Nick Weldon of the Historic New Orleans Collection.

Delegates attempting to meet at the Mechanics Institute that day hoped to set a date for a NEW convention.

“It was a precursor to what would have been a constitutional convention,” says Weldon. “So, the convention had taken place in 1864 and they had passed a lot of things. But one thing that they left unresolved was Black male suffrage. So, some of the radicals who were in the legislature at that time called to reconvene because the war was over.”

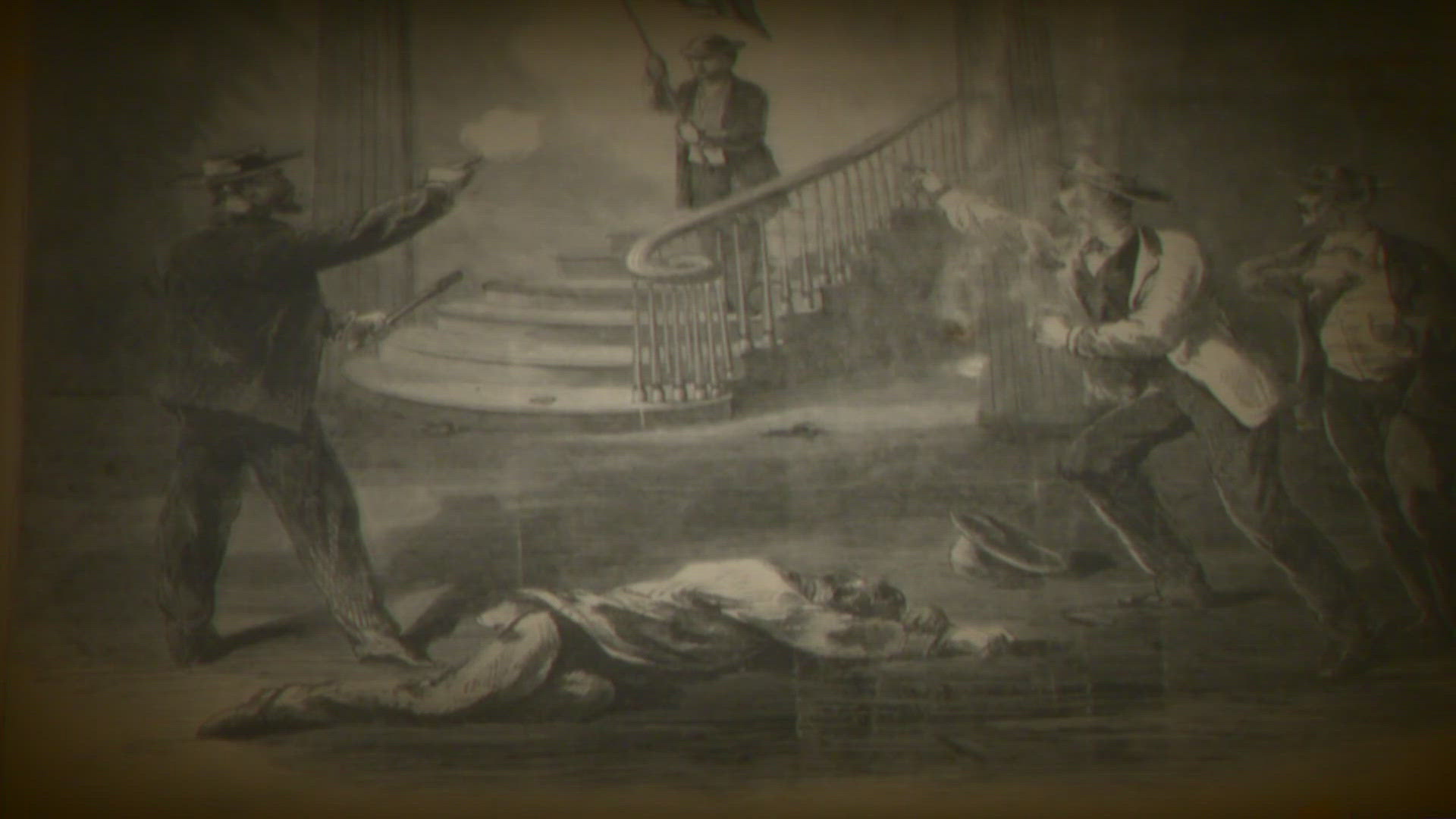

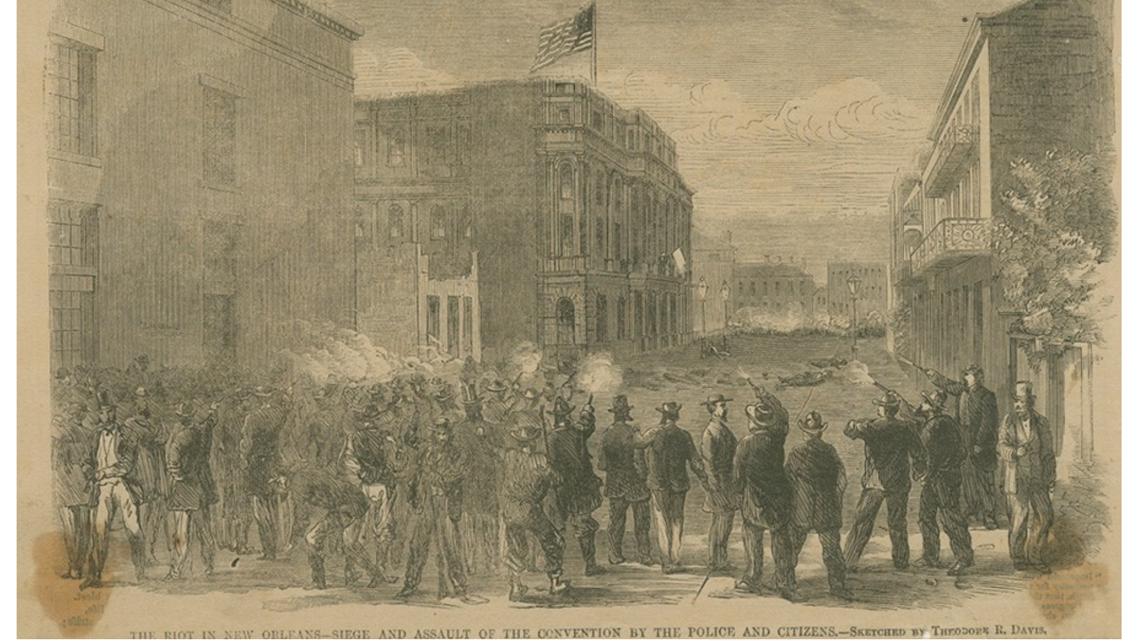

Harpers Weekly, a national magazine based out of New York City, drew illustrations depicting what led up to the deadly events.

Before that meeting could take place, almost 200 Black men, reportedly unarmed military veterans, paraded up Canal Street to show their support for Black suffrage. As they approached the Mechanics Institute, they were immediately met with violence by a white mob of former confederates, police officers, and firefighters who were sent by then-New Orleans Mayor John Monroe, who was also a Confederate sympathizer.

“Almost immediately, they began firing upon the marchers,” says Weldon. “So what we see here are scenes of what happened after the Black marchers came into the hall. There were White supporters and delegates in the convention. You can see here it was just complete violence; the marchers and the delegates were defenseless.”

Congress sent a delegation to interview witnesses of the massacre, and their report laid the groundwork for sweeping national changes. Radical Republicans would swiftly take office, leading to the Reconstruction Acts.

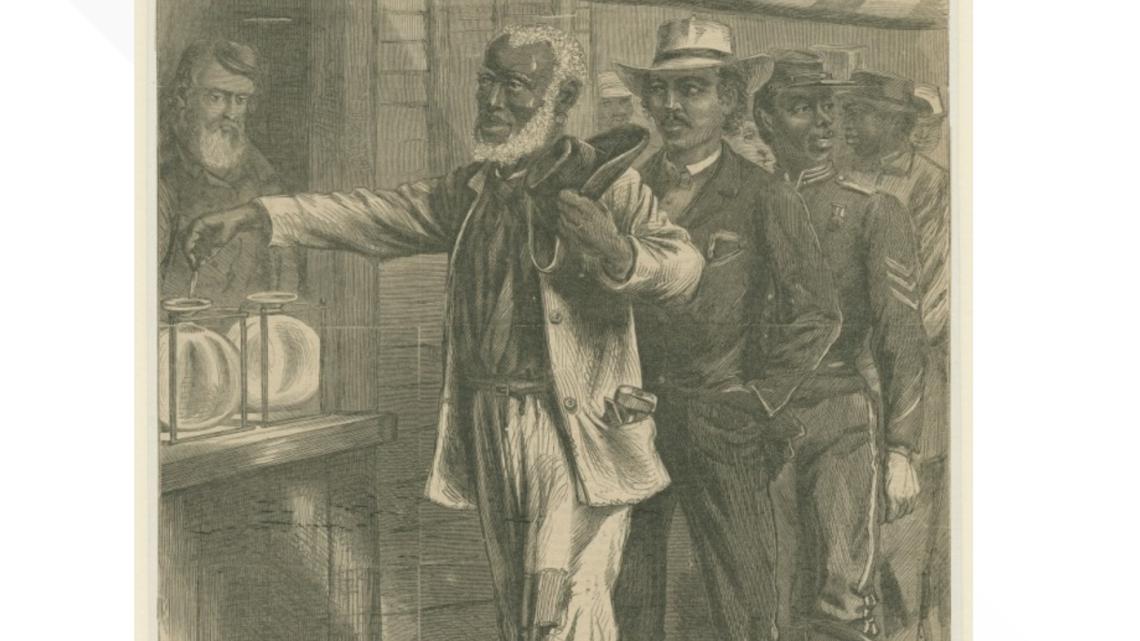

“So, this leads to the ratification of what we call the Reconstruction amendments. Beginning with the abolition of slavery, the 14th and 15th Amendments were passed; the 15th was eventually ratified by 1870. So, this all influenced the national kind of political tenor that enabled these amendments to the constitution to be passed.”

It also disenfranchised supporters of the confederacy in public office and enabled a lot of Black men to attain legislative office.

While publications of that dreadful time in American history give us a glimpse into the country's difficult transition into the reconstruction era, the only monuments that seemed to go up represented the fallen confederacy with no mention of the Black men and women who perished during the massacre. However, they paid for the freedoms of Black people across the country with their lives.

“158 years have gone by and they have not been recognized, says Keith Plessy, Co-Founder of the Plessy and Ferguson Initiative and a descendant of Homer Plessy.

The organization worked alongside others to put up a marker to finally recognize their sacrifice. It's just one of several markers they've placed around the city marking historical events in Black history. Though the buildings no longer stand, the true story remains and can now be shared for generations to come.

“We intend to take the history because it has been whitewashed so much for our events that happened in history that should be recalled,” says Plessy. “The main goal we are trying to reach is unity within the city and the state.”

Unity during a time of political peril so more than 150 years later, we can avoid history repeating itself.

Fatima Shaik, author of "Economy Hall: The Hidden History of a Free Black Brotherhood, has firsthand accounts of what some members witnessed at the Mechanics Institute that day. Below she shares what she found while going over hundreds of documents.