NEW ORLEANS — On Monday, big news came out of Massachusetts. Biotech firm Moderna announced that its trial vaccine triggered an immune response in the first people it was tested on.

Other studies out of England and China are also on the fast track, but scientists worldwide say there are still uncertainties and larger clinical trials are needed to see if these vaccines can actually protect people.

And as the vaccine race continues at record speed, we checked in with a local doctor, who is working on a vaccine for his take on the news.

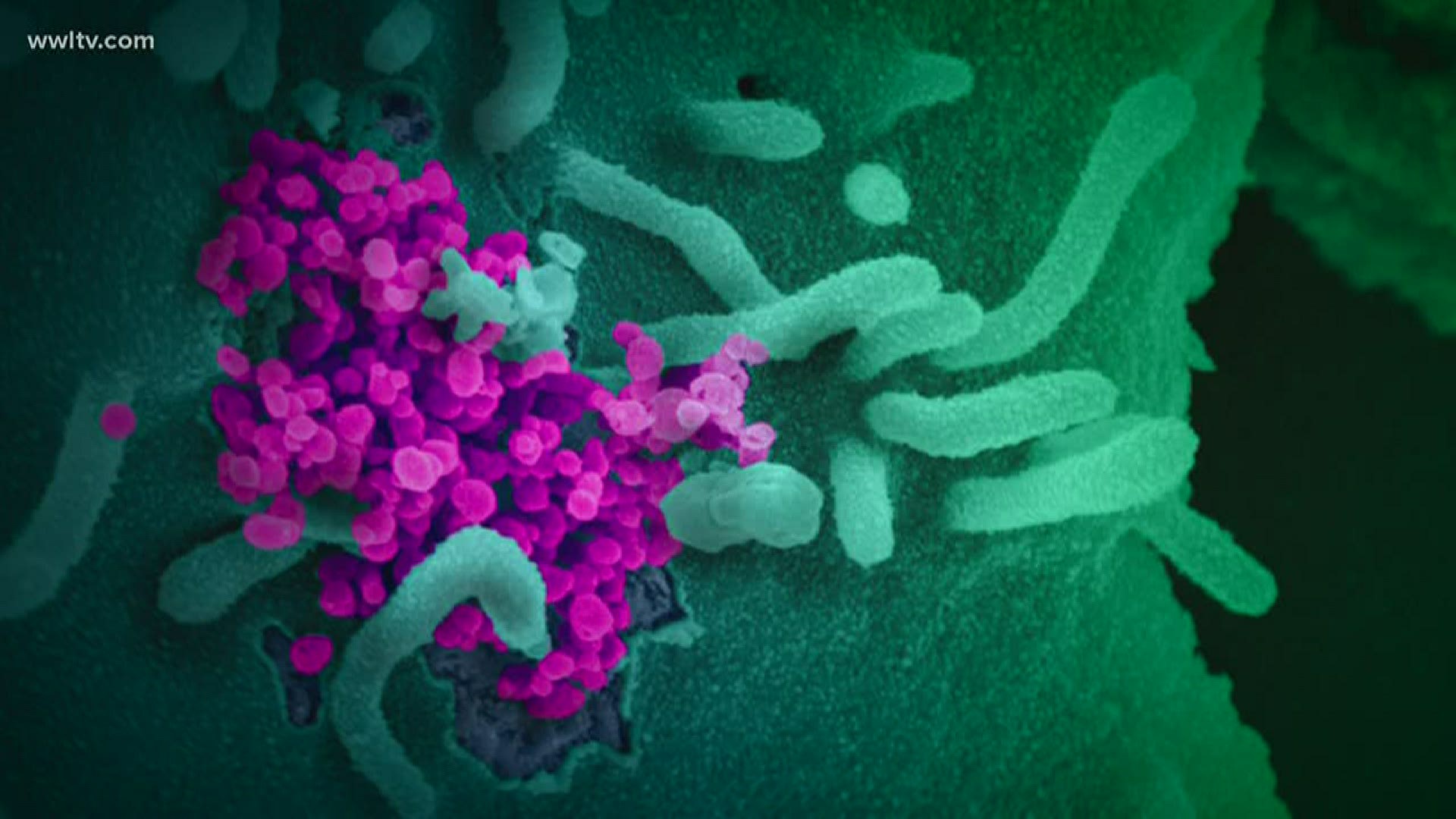

As chief veterinary medical officer of the Tulane National Primate Research Center, Dr. Skip Bohm is one of the doctors working on a vaccine for the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, and the number one question he gets is when will one be ready from any company.

"I don’t think we’ll have one by the end of the year, but I’m hoping that I’m wrong there," Bohm said.

But he thinks a vaccine by early 2021 is possible and believes scientists are on the right track.

"I’m optimistic, and my colleagues are optimistic that we’re going to have a vaccine. There are over 100 vaccines that are known to be in the pipeline, and I think there are plenty more than that out there that we just don’t know about. They're private companies in biotech that are working hard," he said.

Dr. Bohm says the fastest vaccine was for Ebola took four years. Typically, vaccine development can take 10 or more years. The speed of developing this one is unprecedented. It's the fastest the world has seen.

"There is far more collaboration on a wider scale than there has been in the past and what that does is it expedites what we learn and how quickly we learn things," Dr. Bohm explained, referencing the world sharing of preliminary data.

He would not want to be one of the volunteers who are among the first to get a vaccine in clinical development.

"I would say you have to be brave to do this, and I think most people that do that feel that they’re helping mankind and it’s true."

In Covington at the Tulane Primate Center, Dr. Bohm and his colleagues are successfully studying infected primates. They get infected as we do, from airborne droplets and contaminated surfaces, and shed the virus like humans from the nose and throat for a long time.

"Another thing that was similar to humans is that most of the animals didn’t get sick, visibly ill, but there were a couple that did."

And those were the older primates.

He says all of these tests are necessary steps towards developing a vaccine.

In that Massachusetts study, the company, Moderna, reported that 45 study participants who got the experimental vaccine developed a strong immune response to the virus.

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.