NEW ORLEANS — Some of the best insight into why kids turn to crime and violence comes from the kids themselves.

“It was a lot of anger with me, you know what I'm saying, with my mom being on crack,” said Russell, now in his 20s, fresh from a four-year prison term. “I'm going to school with the cheapest clothes, the cheapest shoes. Just being bullied, being ridiculed.”

With his father working two jobs, Russell was determined to become more independent. He started selling marijuana as a young teenager.

“Next thing you know, my clientele got bigger and bigger and bigger. And I just went from buying quarter pounds to half a pound, I graduated up to a pound,” he said. “The money was just overwhelming, you know. I had never seen that much money at one time coming that fast as a young'un. And I'm able to buy the things that I always wanted.”

Today, Russell is free, but full of regret. Like so many juveniles who turn to crime, there was a host of social and psychological problems that led to his risk-taking behavior. A criminal justice system ill-equipped only made Russell’s situation worse.

The new normal?

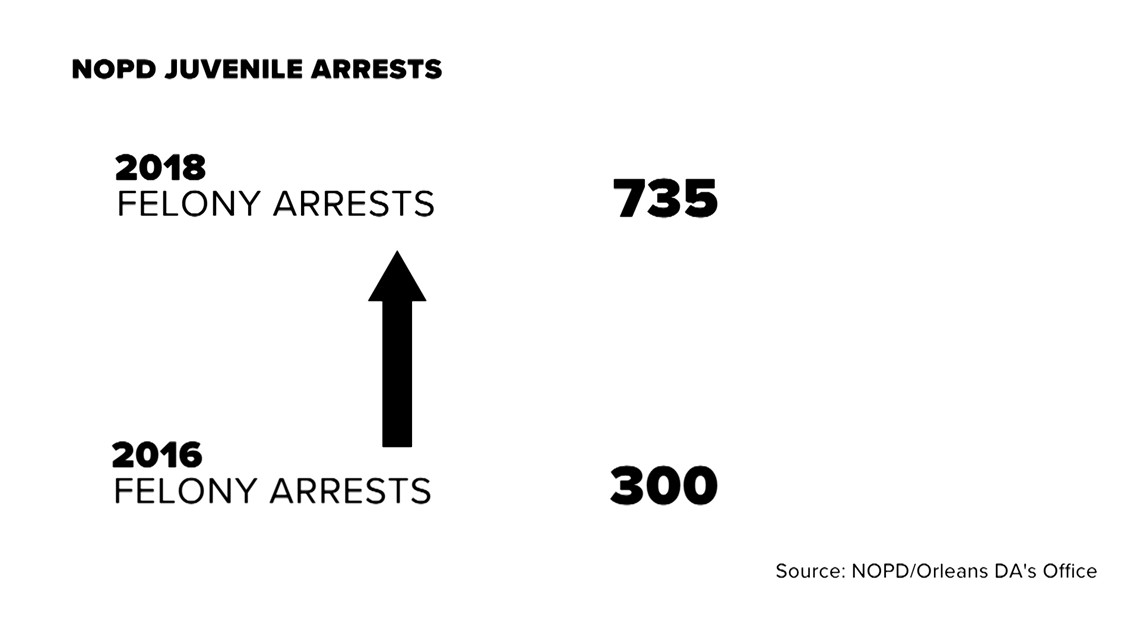

In New Orleans, the juvenile justice system is being tested like never before. New Orleans police reported 1,232 arrests last year, but more troubling was the record number of arrests for juvenile crimes of violence: shootings, stabbings, beatings, killings, robberies and sexual assaults.

The number of violent crimes that passed through Juvenile Court in 2018 was 339, nearly a 10-fold increase from the 37 recorded in 2015.

Orleans Parish District Attorney Leon Cannizzaro called the spike in teen violence “the biggest local crime issue” facing the city.

Mayor LaToya Cantrell also identified the problem as a top priority.

“We cannot impact in any way public safety effectively if we don't address juvenile crime,” said Mayor LaToya Cantrell at a recent press conference announcing new programming at the Youth Study Center, the lockup for juveniles.

“(We need to) give our young people what they truly deserve so that we are ensuring that they are getting a holistic approach to building them up," Cantrell said.

While these two city-wide elected officials agree on the problem, they are divided on how to attack it.

Cannizzaro and other officials, including many police officers, see a juvenile justice system that acts as a revolving door for troubled youths, with some kids building criminal rap sheets that eventually explode into violence.

Cantrell, however, is advocating for less detention. She favors adopting the national reform trend toward less incarceration and more community-based rehabilitation.

The stakes are as high as the crisis is daunting.

In 2018 alone, the city was hit with a virtual wave of armed robberies and carjackings by youngsters 16 and younger. Seven juveniles were arrested in a string of armed robberies. A 13-year-old accused of trying to carjack an undercover state trooper. A group of kids as young as nine terrorizing the Bywater and Marigny with brazen burglaries.

In one galvanizing tragedy in December, three teens were arrested in a carjacking that took the life of Jeannot Plessy, the wife of a local pastor. One suspect was 15.

Behind the crimes

Behind many of the juvenile offenders are gut-wrenching stories of broken homes, poverty, troubles in school, physical and sexual abuse, untreated mental illness, prescription and non-prescription drug abuse.

LSU professor Stephen Phillippi, an expert in adolescent trauma and delinquency, says these childhood land mines can lead to criminal behavior including extreme violence. He says juveniles can be especially volatile because their brains are still developing, especially the areas responsible for decision-making, the frontal lobes.

“Their preference for risky behavior is at its all-time high during adolescence,” Phillippi said. “The frontal lobes of the brain aren't fully developed until your early 20s. So what does that mean? It translates into poor impulse control, very high susceptibility to peer pressure.”

In a series of interviews with four former juvenile offenders, WWL-TV captured Phillipi’s clinical warning signs in harrowing true-life detail.

“I started getting in trouble at school….My mom got her rights taken away as a parent….I started acting very violent,” said Tyler, now 21.

Tyler's rap sheet begins at age 10, when he was arrested for arson. Then, while confined to a group home, he attacked a staff member.

“I had hit him with a brick. I had hit him on the side of the face,” he recalled. For the aggravated battery, Tyler served five years in juvenile detention, from age 13 to 18.

While locked up, Tyler joined a gang. His arms are covered with tattoos of the “Blood 5-9”

“I was 13. I was small,” he recalled. “So a lot of guys tried me. You know, mess with me, constantly, constantly. And I just got tired of it. That's mostly what gang affiliation comes with, is protection.”

Mike, now 18, was locked up after he got caught in a series of burglaries.

“Dirt bikes, four-wheelers, watches, phones, games, guns,” said Mike, describing the items he stole. “Whatever we could get our hands to, that's what we were getting.”

Mike’s background was a textbook case of a child at risk: he never knew his father, was raised by his grandmother when his mother left, fell behind in school, saw two of his older cousins fatally shot. Struggling to find his place, Mike said he fell under the influence of an older cousin who led him – reluctantly at first – into a life of crime.

“He said, ‘Man, you a coward,’” Mike recalled. “I had to prove to him that I wasn’t no coward.”

Like Russell, Tyler and Mike spent time in juvenile lockups. While locked up, they said there was more emphasis on controlling their behavior with medication than with counseling or rehabilitation.

“There was really no counseling,” Tyler said. “It was more, putting you on meds.”

Sheri Lochridge, a case manager at Covenant House, a shelter for homeless teen-agers, said she counsels hundreds of young people with similar hardships.

“The common thread is early childhood abuse, poverty, homelessness, neglect,” Lochridge said. “The kids end up in trouble, but there’s no rehabilitation. Nobody’s getting to the root of the matter.”

Another counselor at Covenant House, Tyrone Smith, said he is wary, even fearful, of juveniles who turn violent.

“I'm terrified of them myself,” Smith said. “I'm very cautious of them. Because they're acting out.”

Following the trend

Around the country, there is a push to provide more services to youngsters veering into crime. Detention is giving way to treatment. Isolation is giving way to community programs. Medication is viewed as a last resort. Mayor Cantrell has vowed to take the same approach in New Orleans.

In January, Cantrell introduced two new programs to engage the detainees at the Youth Study Center. At one point, she engaged the young offenders directly.

“You are not throwed away,” she told the detainees. “You matter. You matter. You meet us halfway, and we're going to put you on a path to be successful.”

But there is a major barrier on the city's path to reform: Funding.

Clerk of New Orleans Juvenile Court Ronard Darensburg explains that while counseling and outreach programs have been introduced, funding comes from an inconsistent patchwork of grants and court fees.

He contrasts the city’s situation with Jefferson Parish.

Through a dedicated millage, Jefferson has about three times the money for juvenile justice than Orleans, about $12 million a year compared to $4.2 million in New Orleans. Jefferson arrests a similar number of juveniles each year, but only a fraction of them are violent crime arrests.

“The problem is that it's funding. And we don't have the funds to create the capacity. Imagine if we had $11 million a year to devote solely to juvenile services,” Darensburg said. “Currently, that is nowhere near. We have nothing do deal with juvenile services to be honest with you.”

Phillipi said the same funding disparity holds true for juvenile mental health services.

“When you talk about a lot of these spikes in New Orleans, a lot of those services are right across the parish line in Jefferson at a higher rate of access than we have in Orleans,” Phillipi said.

The problem could get worse before it gets better. A change in the law kicks in this year, eventually sending all 17-year-olds into the juvenile system.

The law begins for non-violent crimes next month, and for all violent crimes in 2020.

Tyrone Smith's approach at the Covenant House, is precisely what is being recommended by reformers, although the shelter is not a formal part of the city's juvenile justice system.

“We need to let them know, we love you. We care about you. We're here to support you,” Smith said. “The light will always come on.”