Does buying a smartphone from certain Chinese brands expose you to spying?

Ordinarily you’d judge the Mate 10 Pro from China's Huawei on its its lovely 6-inch OLED display and exceptional battery life.

But there’s a bigger issue beyond the specs of the flagship handset from the No. 3 phone maker in the world, which has been banking on the $799.99 smartphone to challenge Samsung Galaxy and iPhone in North America.

Lawmakers in the United States have placed Huawei and another Chinese manufacturer, ZTE, in the crosshairs over their reputed ties to the Chinese intelligence and military establishment.

U.S. officials' concern is that their products could be conduits for Chinese espionage, both on a targeted and a grand scale. Both handset makers have denied any such complicity.

At this week's Mobile World Congress, where both companies have a large presence, Huawei CEO Ken Hu told reporters such concerns are "groundless suspicions," according to Reuters.

Spy claims

Hu is countering increasingly vocal opposition to Chinese technology companies from some parts of the U.S. government.

This month, when Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) asked the heads of the CIA, FBI and four other intelligence chiefs to their raise hands if they would recommend that private American citizens use Huawei or ZTE products or services, none did.

Rep. Mike Conaway, R-Texas, introduced a bill to prohibit the U.S. government from purchasing or leasing telecom equipment from Huawei and ZTE.

And last month, just before Huawei was set to promote the Mate 10 Pro during the CES trade show in Las Vegas, a deal with a U.S. carrier believed to be AT&T for the phone was scuttled, apparently because of pressure from U.S. government officials. Verizon had also reportedly been in talks with Huawei.

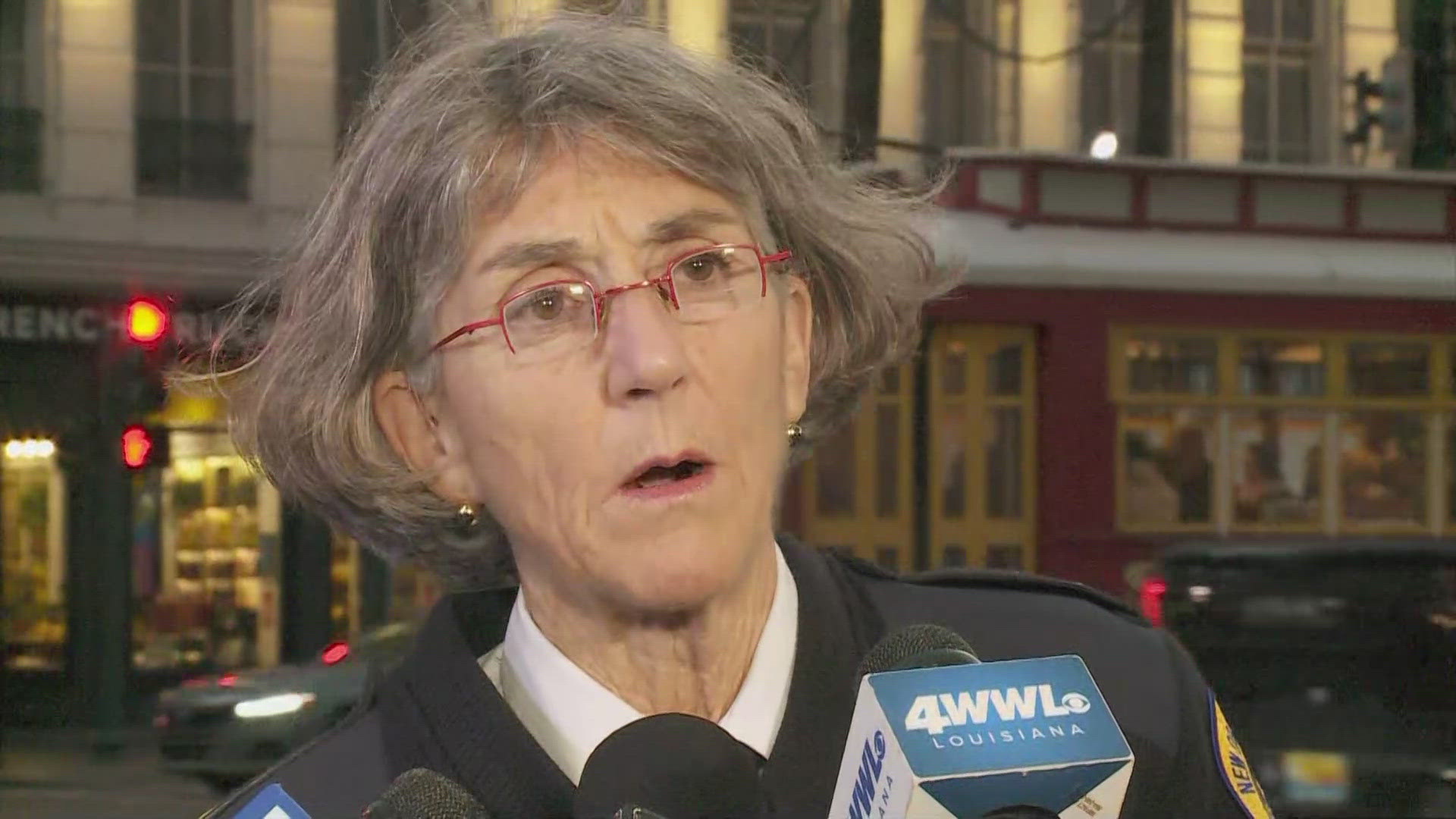

At Mobile World Congress, Verizon Wireless senior vice president and chief network officer Nicola Palmer declined to elaborate on the carrier's relationship except to say that "we don't have Huawei equipment in our network and don't have plans to."

While no evidence of cyberspying from either Huawei or ZTE has been presented to the public, the idea of cybersnooping involving the Chinese is not without precedent.

Blu phones spyware

In 2016, security firm Kryptowire said tens of thousands of mostly inexpensive Android phones, including the BLU R1 HD sold at Amazon from a Miami-based company that was selling rebranded Chinese phones, were secretly transmitting text messages, contact lists and call logs to servers in China. Such phones came preloaded with firmware managed by a company named Shanghai Adups Technology Co.

At the time, a lawyer representing Adups told The New York Times, “This is a private company that made a mistake.”

Blu subsequently removed the offending software. Along the way, the Blu phones were removed, then eventually reinstated on Amazon. The issue surfaced again in July when Amazon pulled the phones over spyware. After apparently determining that it was a false alarm, Amazon again put the phones on sale.

Last year, ZTE agreed to pay $892 million to the U.S. government as part of a settlement of claims that it violated sanctions on Iran. While it wasn't a cybersecurity issue per se, attorney general Jeff Sessions said at the time the export controls that were violated aim "to keep sensitive American technology out of the hands of hostile regimes like Iran’s."

“The only thing that gives me any pause is that lawmakers have access to classified information," says Jamie Winterton, Director of Strategy for Arizona State University’s Global Security Initiative. "They may have a reason for picking out these two particular companies and saying we don’t want these particular phones released in the United States.”

But while Winterton believes there is a general concern with hardware security, she added, “I don’t think that that concern is solved by banning phones from companies in China.”

'Committed to openness'

Huawei insists it follows the rule book in the countries in which it operates. In a statement to USA TODAY, the company indicated that it “is aware of a range of U.S. government activities seemingly aimed at inhibiting Huawei's business in the U.S. market."

"Huawei is trusted by governments and customers in 170 countries worldwide and poses no greater cybersecurity risk than any (communications) vendor, sharing as we do common global supply chains and production capabilities. We are committed to openness and transparency in everything we do.”

In its own emailed statement, ZTE says it stands behind the security of its products in the U.S. market and includes U.S. made chips and other components in its phones.

"As a publicly traded company, we are committed to adhering to all applicable laws and regulations of the United States, work with carriers to pass strict testing protocols, and adhere to the highest business standards," the ZTE statement said.

Huawei and ZTE are by no means the only Chinese phones sold in the U.S. Even a venerable U.S. brand name such as Motorola is now owned by China’s Lenovo, which in September settled with the Federal Trade Commission over charges it shipped some of its laptops preloaded with software that compromised security, related to delivering ads to consumers.

When it comes to phones, popular handsets including Apple’s iPhones and Samsung’s Galaxy’s include parts sourced from China. China is also where some of the phones are assembled.

Is that an important distinction? Dean Cheng, senior research fellow for Chinese political and security affairs at the Heritage Foundation, says the mere fact that companies (such as Huawei and ZTE) are Chinese means they will "respond to recommendations and advice" — read pressure — from the central Chinese government.

Even with the recent concern from Congress over Chinese technology, it's still very easy to buy a Chinese cellphone in the U.S. to use here. Without a carrier deal, you can buy an unlocked version of the Huawei Mate 10 Pro at Amazon, Best Buy and other electronics retailers, then insert your own SIM card to use the device.

ZTE sells its own phones in the U.S., several budget models, as well as the foldable dual-screen Axon M smartphone.

Tolerating risk

Part of whether to buy one boils down to your own tolerance of risk and belief that your personal information will end up in the hands of a state actor, Cheng says.

“We have pretty good evidence that the Chinese take a Hoover vacuum approach towards information collection,” he says.

As a typical consumer you may not think you need to be on guard, especially if you're not employed, say, by a defense contractor or aerospace company or work for a firm that does business in China.

Still, Galina Datskovsky, CEO of Vaporstream, a secure messaging company in Chicago, says you ought to think about “who you know, what you know, where do you work, where does your family work, where do your friends and contacts work, (and) with whom are you corresponding.”