This story is part three of a three-part series exploring the infamous "Cancer Alley" along the river parishes of southeast Louisiana. Click here to read part one. Click here to read part two.

The seven-parish corridor between metro New Orleans and Baton Rouge is home to at least 83 chemical plants and the federal government has found it has some of the highest toxic emissions in the U.S.

But even after a recent federal study found the risk of getting cancer from breathing the air there is among the highest in the nation, chemical companies and Louisiana officials continue to question the validity of the name “Cancer Alley.”

“Actual cancer incidence data from the National Cancer Institute State Cancer Profiles show liver and lung cancer rates in St. John the Baptist Parish are well below both the Louisiana and national averages,” said a statement from DuPont, which ran a chemical plant in St. John for 46 years until 2015, selling it just one month before the Environmental Protection Agency identified it as producing the highest cancer risk in America.

“We have annual health checks and all kinds of facilities to make sure we’re OK, so I’m not sure where the term Cancer Alley came from and wouldn’t have any more comments around that,” said Jorge Lavastida, a former DuPont employee at the St. John plant who now manages it for the Japanese company Denka Performance Elastomers. The plant makes the synthetic rubber Neoprene and emits the chemical chloroprene in far higher amounts than anywhere else in the country.

“A year ago, I hadn’t heard the word chloroprene or dealt with that in Louisiana, but it’s been here,” Louisiana's State Health Officer Jimmy Guidry told the St. John Parish Council in 2016 -- a strange admission from the state's top health official six years after chloroprene was declared a likely human carcinogen by the EPA.

But then, Guidry went on to dismiss chloroprene's dangers.

“It’s been here, it’s been here for a long time, so you would expect if there were high levels and spikes, you would expect higher levels of cancer from if the exposure had been high enough, and we’re not seeing that.”

These arguments are the latest effort to downplay the risks of air pollution coming from plants all along the Mississippi River. They rely on the LSU Tumor Registry, which collects data about cancer diagnoses. These officials and industry representatives say the EPA assessment of cancer risk must be faulty because the Tumor Registry is unequivocal in finding average or below-average cancer rates in the Cancer Alley corridor.

Nowhere is the disparity between cancer risk and actual cancer incidence rates more notable than in St. John. The risk of getting cancer from breathing in chloroprene and other toxic chemicals in the air in the neighborhood directly adjacent to the DuPont-Denka plant is a staggering 826-in-a-million. Averaged out for the whole parish, the risk is 254-in-a-million.

Only about 130 of the nation’s 73,000 neighborhoods have a higher than 100-in-a-million risk, and seven of the Top 10 riskiest are in St. John.

But the LSU Tumor Registry finds St. John’s age-adjusted cancer rate is 463 per 100,000 residents, higher than the national average of 444, but well below the Louisiana average of 479.

Bobby Taylor grew up in St. John and moved to California as a young man. But he came back to stay in 1994 when his mother was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer.

Taylor’s family home is just blocks from the DuPont-Denka plant.

“I did a lot of traveling when I was living and working out of Los Angeles and everywhere I went I heard about Cancer Alley,” he said. “I had never heard of that and I lived here.”

And environmental activists say that’s part of the problem. Residents are kept in the dark about the dangers, often until it’s too late.

Anne Rolfes of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade has been advocating for communities along the fence lines of chemical plants for 20 years. She said a 1984 chemical release in Bhopal, India, which killed more than 2,000 people and injured an estimated 500,000 awakened concern in permissive Louisiana.

Chemical workers started to align with environmentalists. In 1984, workers at a BASF plant in Geismar put up a billboard on Interstate 10 calling their plant “Bhopal on the Bayou.” In 1988, the labor union put out a video calling attention to chemical exposure at the plants and teamed with Greenpeace activists to hang a banner reading “Cancer Alley” on the I-10 Mississippi River bridge in Baton Rouge.

“The name ‘Cancer Alley’ has stuck. And it’s stuck for a reason. Because it’s true,” Rolfes said.

But Louisiana Environmental Quality Secretary Chuck Carr Brown disagrees. He trusts the Tumor Registry data over the EPA’s assessment of risk.

The Tumor Registry “have been collecting data for over 50 years, they collect it from every source,” Brown said.

And he discounts anecdotal complaints from residents near the plants, who say their neighbors and families are being hit with an inordinate amount of cancer, chronic respiratory illnesses and unexplained autoimmune diseases.

“You can walk up any street and knock on any door and you can ask the question, ‘Has anybody in this house had cancer?’ And the answer is going to be yes,” Brown said. “That’s 100 percent. But is that really a statistically significant method of collecting data?”

Lavastida, the Denka plant manager, also questions the EPA’s method of calculating the risk to humans of breathing in chloroprene. He says the EPA’s tests on rats and mice are not properly applied to humans. He and Denka have argued that 31.2 micrograms of chloroprene per cubic meter of air is a safe level for humans to breathe over a lifetime, 156 times higher than the 0.2 micrograms per cubic meter guidance set by the EPA.

But Rolfes and others question the validity of the Tumor Registry data, too.

“If you have an institution that’s not fully funded and is not doing a thorough job of understanding cancer from the point of view of the people who are sick, then to me that agency does not have the accurate statistics,” she said. “I haven’t seen anything that shows me their investigations are robust.”

This argument isn’t new. Investigations in the 1990s found the cancer incidence data was being collected in a way that may conceal the real rate of cancer in areas closest to the chemical plants. The Tumor Registry has repeatedly declined to turn over data that’s more specific than parish-wide averages, even going to court to argue that privacy laws protect information at the Zip code level.

Until a 2001 agreement with the state, the Tumor Registry wasn’t counting some cancer diagnoses made outside Louisiana, even though a significant portion of Louisiana patients were traveling to Memphis and Houston for treatment.

Concern about the Tumor Registry’s methods even led to a new law, passed by the State Legislature in 2017. It requires the Tumor Registry to provide data more readily and to report cancer rates at the census tract – or neighborhood – level, not just by parish.

The Tumor Registry declined to be interviewed for this story, but it stands by its data collection and reporting methods. The new census tract data should come out in the spring, and it could explain the vast differences between the EPA’s neighborhood-level risk data and the number of cancer cases reported at the parish level by the Tumor Registry.

But residents and activists still question if communities that are traditionally underserved by health care providers will be fully counted.

“When you look at the map at most of these industries, you’ll see that it will be poor, primarily black people who are affected by it,” Taylor said.

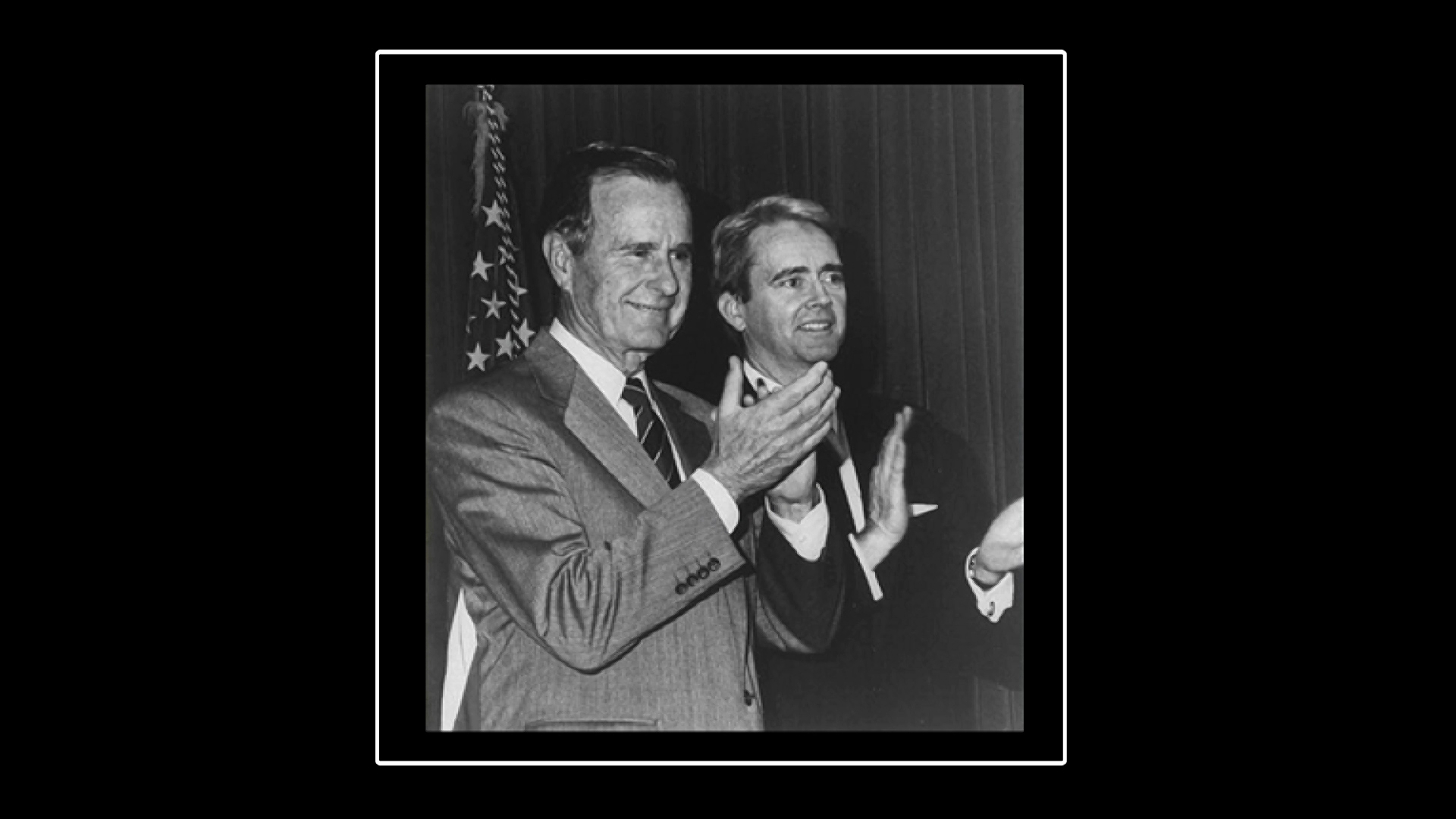

William K. Reilly, former President George H.W. Bush’s EPA administrator in the late 1980s and early 1990s, said racial and economic disparities have a real impact on environmental justice.

“We called it Environmental Equity, which I established at EPA as a priority and an office,” Reilly said. “And Cancer Alley was one of probably a dozen places where there were claims on the part of residents.”

Reilly said he sent EPA researchers into those communities, but they found it difficult to prove a correlation between the illnesses and the pollution from neighboring plants.

“When they did statistical analyses of the incidences of disease and compared it with averages elsewhere, they were not able to confirm those claims,” Reilly said.

The government has more work to do, he said.

“I think it really behooves an agency … to get to the bottom of that. And that means conducting some pretty thorough and probably expensive – but certainly more extensive – research than we have.”

Rolfes says there’s another way to tell if plants like DuPont-Denka are polluting the air at safe levels or not.

“Where does the plant manager of Denka live? I assure you he does not live right next to his facility. And up and down the Mississippi River, that’s true,” Rolfes said.

Lavastida, the Denka plant manager, acknowledges he commutes from Baton Rouge.

“That’s a fair comment,” he said, responding to Rolfes’ question.

But Lavastida has also spent 28 years working many hours inside chemical plants, and he’s convinced the companies do what’s necessary to keep their workers and the surrounding communities safe.

“We have annual health checks and all kinds of facilities to make sure we’re OK, so I’m not sure where the term Cancer Alley came from and wouldn’t have any more comments around that,” he said.

Kevin Dupuy contributed graphics and visualizations to this story.