This story is part one of a three-part series exploring the infamous "Cancer Alley" along the river parishes of southeast Louisiana. Click here to read part two.

---

NEW ORLEANS – Neoprene is not exactly a household word, but it’s certainly made its way into most U.S. homes.

It’s a synthetic rubber used in hoses, mouse pads, leggings, yoga mats, wetsuits and Halloween masks. The main chemical used to make neoprene is chloroprene, and it is only produced in one place in the country: the Dupont-Denka plant just upriver from New Orleans in St. John the Baptist Parish.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says chloroprene is being released into the air in large quantities there, and the chemical is likely a cause of cancer.

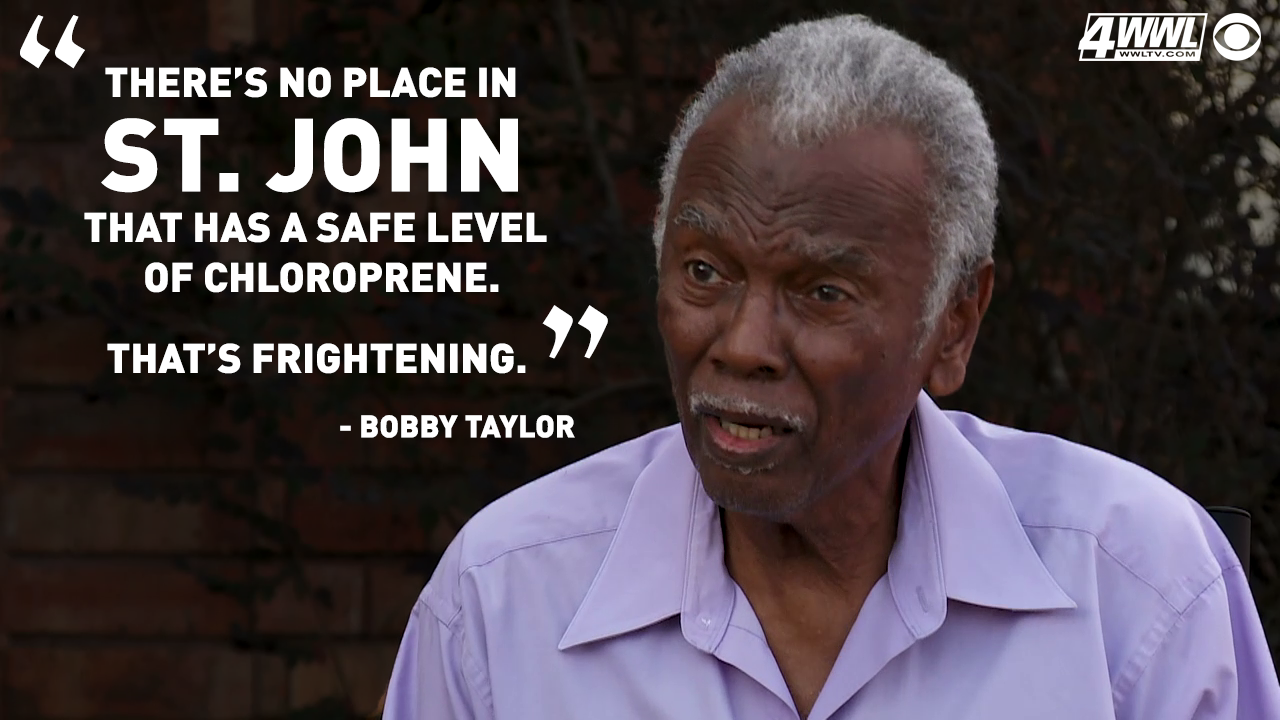

“It’s permeating the whole parish,” Bobby Taylor said. “There’s no place in St. John that has a safe level of chloroprene. Man, that is frightening.”

Taylor formed the Concerned Citizens of St. John after seeing rare forms of cancer and other illnesses affecting his neighbors.

“This family right here lost the mother and the father and now the two sons are affected with the same cancer. This family lost people to cancer. Two of the people in that household lost people. I lost my mother and my brother, and my nephew, and my niece.”

When the EPA became concerned about chloroprene emissions, Taylor suspected the chemical was behind the illnesses. In 2010, the EPA set 0.2 micrograms per cubic meter as an acceptable concentration of chloroprene when breathed in over a lifetime. It also officially declared chloroprene “likely to be carcinogenic to humans” based on multiple experiments on rats and mice.

In 2011, the EPA did a toxic-air assessment to measure the airborne cancer risk for every one of the nation’s 73,000 census tracts – essentially measuring the risk from breathing the air, neighborhood by neighborhood. The EPA’s stated goal is to keep the risk of getting cancer to below 1 in a million. But no census tract in the country achieves that low a risk. The lowest recorded risk in remote areas of Colorado is about 10 in a million, and the national average is about 40 in a million.

The EPA’s National Air Toxics Assessment (NATA) map, released in 2015, marks census tracts with a greater than 100-in-a-million risk in red. There are only a few tiny red dots on the map in places commonly associated with air pollution – like smoggy Los Angeles or in New York City, right at the point where traffic gets on and off the George Washington Bridge and enters or leaves downtown Manhattan.

But there is one cluster of noticeable red on the map, in St. John the Baptist Parish. In fact, the top five areas of risk in the entire country and seven of the top 10 are in St. John, all around a single source: the DuPont-Denka Plant.

If 1 in a million is the goal, the neighborhood closest to the plant is 800 times riskier for cancer exposure over a lifetime. The census tract just east of the chloroprene plant has a risk of almost 500 in a million. Another to the north of the plant is almost 400.

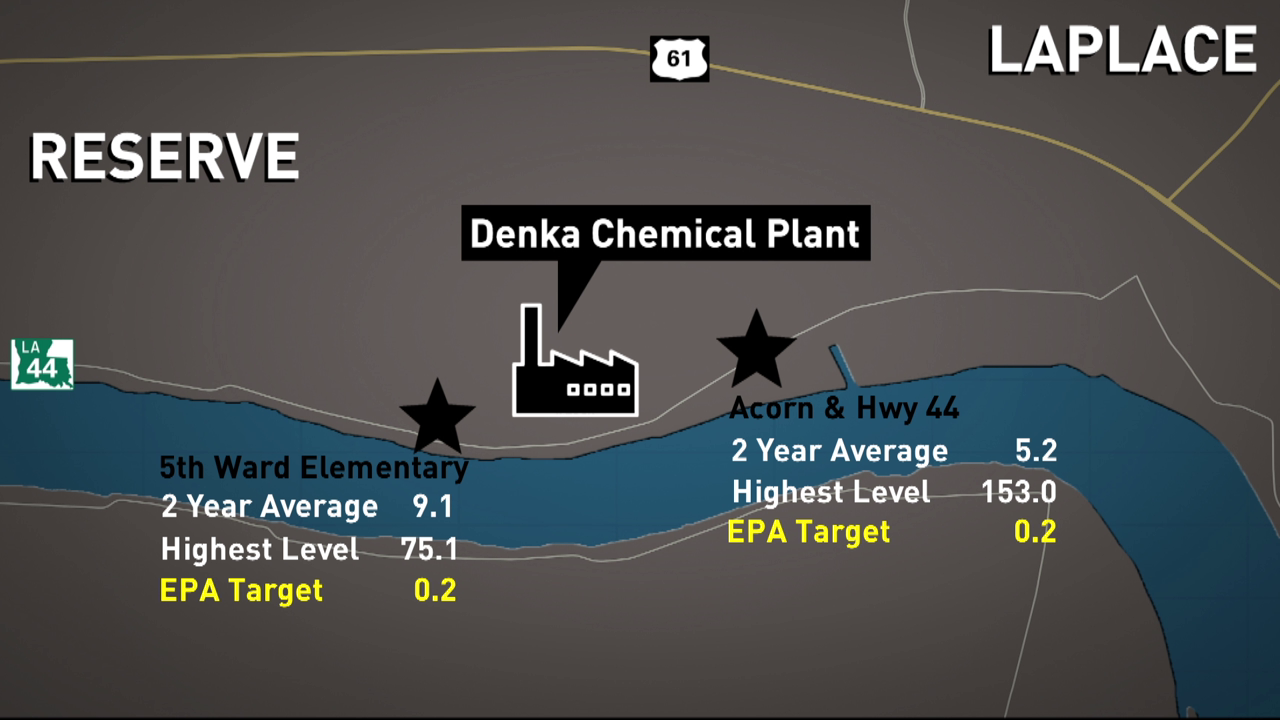

After releasing those findings, the EPA began collecting air samples at six monitoring sites around the DuPont-Denka plant in 2016.

The average chloroprene levels measured over the last two years are high -- more than 40 times higher than the EPA's acceptable level at the monitors located closest to the plant.

But the highest single-day readings are staggering. A 2016 reading at Acorn Street and Highway 44, east of the plant, measured 153 micrograms of chloroprene per cubic meter, which is 765 times the acceptable level if inhaled over a lifetime.

A one-day reading in 2017 captured 75 micrograms per cubic meter at the Fifth Ward Elementary School, a level 375 times greater than the 0.2 threshold. That caused heightened concern from residents who feared that small children would not be able to handle such exposure.

“We have children in schools here where the chloroprene level is 300 times the guidance; 300 times!” said John Cummings, an attorney representing neighbors in a lawsuit against DuPont and Denka. “And it’s not a workman working eight hours a day. These kids, these kids breathe it there, they breathe it at their homes and of course, their little bodies are more susceptible than ours would be.”

“Maybe this is what caused my autoimmune disease, because how else would I get this?” said Taylor’s daughter Raven, who lives just a few blocks to the west of the plant.

Raven had a promising nursing career until she got a rare illness that left her home-bound, her intestinal tract paralyzed.

“Why would I get this? Considering the location where I grew up and the plant, we just kind of figured it out. It has to be,” she said.

Not according to DuPont and Denka.

DuPont was the company that invented neoprene in 1931. For decades, it said the chloroprene in the air was safe. But DuPont filed a 1941 memo with the EPA in 1992, and it shows tests on dogs and guinea pigs 50 years earlier found chloroprene toxic, even deadly, in high doses.

“I have seen evidence that they knew about it since 1941,” Taylor said.

While disclosing the 1941 tests in the 1992 correspondence to the EPA, DuPont complained that the government was unfairly and “unilaterally” imposing new minimum reporting standards. The company also disputed the EPA's assertion that chloroprene had a “significant” impact on the community.

And 23 years later, just as the EPA’s air toxics assessment was about to be released, DuPont sold the chloroprene operations to Denka Performance Elastomers.

In a statement to WWL-TV, DuPont said that during its 46 years producing chloroprene at what it calls its "Pontchartrain" plant, it always kept emissions within the legal limits. It cited worker safety standards set by the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), which limits chloroprene exposure over an 8-hour workday to 857 micrograms per cubic meter of air.

"During our years of operations, DuPont protected our workers from chloroprene exposure applying standards that were up to 125 times more stringent than OSHA standards," DuPont said. "DuPont also operated under an air permit issued by the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ), which established chloroprene emission limits, and we met the Louisiana Toxic Air Pollutant Ambient Air Standard for chloroprene."

Before selling the plant in 2015, DuPont argued the EPA was using higher-than-appropriate toxicity levels for chloroprene when it measured the risk from inhaling it.

And Denka picked up the fight where DuPont left off. The Japanese firm asked the EPA to raise the 0.2 emissions target for chloroprene.

President Barack Obama’s EPA said no in 2016, but when President Donald Trump’s EPA Secretary Scott Pruitt took over last year, Denka tried again. Pruitt spent his first year rolling back clean air and water regulations, but his EPA gave Denka the same answer in January 2018, standing by the 0.2 microgram level and the designation of chloroprene as a likely carcinogen. The EPA even noted that its assessment of chloroprene’s risks had been reviewed by the White House.

The state of Louisiana, however, has been more accommodating and even dismissive of the EPA recommendations.

“Now, keep in mind, EPA still hasn’t set a standard yet. It’s mainly a guidance,” Louisiana Environmental Quality Secretary Chuck Carr Brown said.

Brown said the EPA assessments were cause for concern, and since taking over as DEQ secretary in 2016, he’s made several presentations to St. John the Baptist Parish leaders about the issue. But during those presentations, he has accused some activists of overstating the dangers of chloroprene and “fear-mongering.”

Environmentalists like Anne Rolfes of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade are firing back at Brown, a former Exxon employee.

“Our state should be in there protecting people and instead, our state Department of Environmental Quality chief is calling people names, people who are concerned, and he’s in there defending industry, which has unfortunately been his entire career,” Rolfes said.

Brown said he was just reacting to flyers that told residents they were breathing “poison” air, but he apologized for using the term “fear-mongers.”

“I wish I had not used that term. But instead of fanning the flames, we need to be working together for a solution that’s protective,” Brown said.

Brown and the Louisiana DEQ did get Denka to agree in 2016 to cut its chloroprene emissions by 85 percent. Denka says it spent $30 million last year installing new equipment to better control the chemical releases.

Map showing the cancer risk in all Louisiana parishes

Brown said he wants to keep any new regulations rooted in science. He said he’s focused on protecting human health. WWL-TV asked if he is also trying to protect the chemical companies’ bottom line. He said he isn’t, but said he can’t promulgate any new regulations until he knows exactly how much Denka can reasonably reduce emissions.

“Let me collect some more data. Let me see exactly what we’re getting out of the back end, then let LDEQ and EPA will agree on a path forward,” Brown said.

Denka said it’s still working out the kinks in the emissions-reduction equipment. Brown said he’s expecting to start collecting data on the fully reduced emissions in March.

But neighbors say they’ve waited long enough.

“We didn’t know a lot about relating it to my disease until we found out how horrible the levels were,” Raven Taylor said. “And then, when I think about a doctor asking me if I had issues from childhood, I said ‘no.’ But apparently, I really believe I did.”

She believed it, but what does the science say about the connection between neighbors’ illnesses and the chloroprene? We’ll have that story Friday on WWL-TV.

-- Kevin Dupuy contributed graphics for this story.