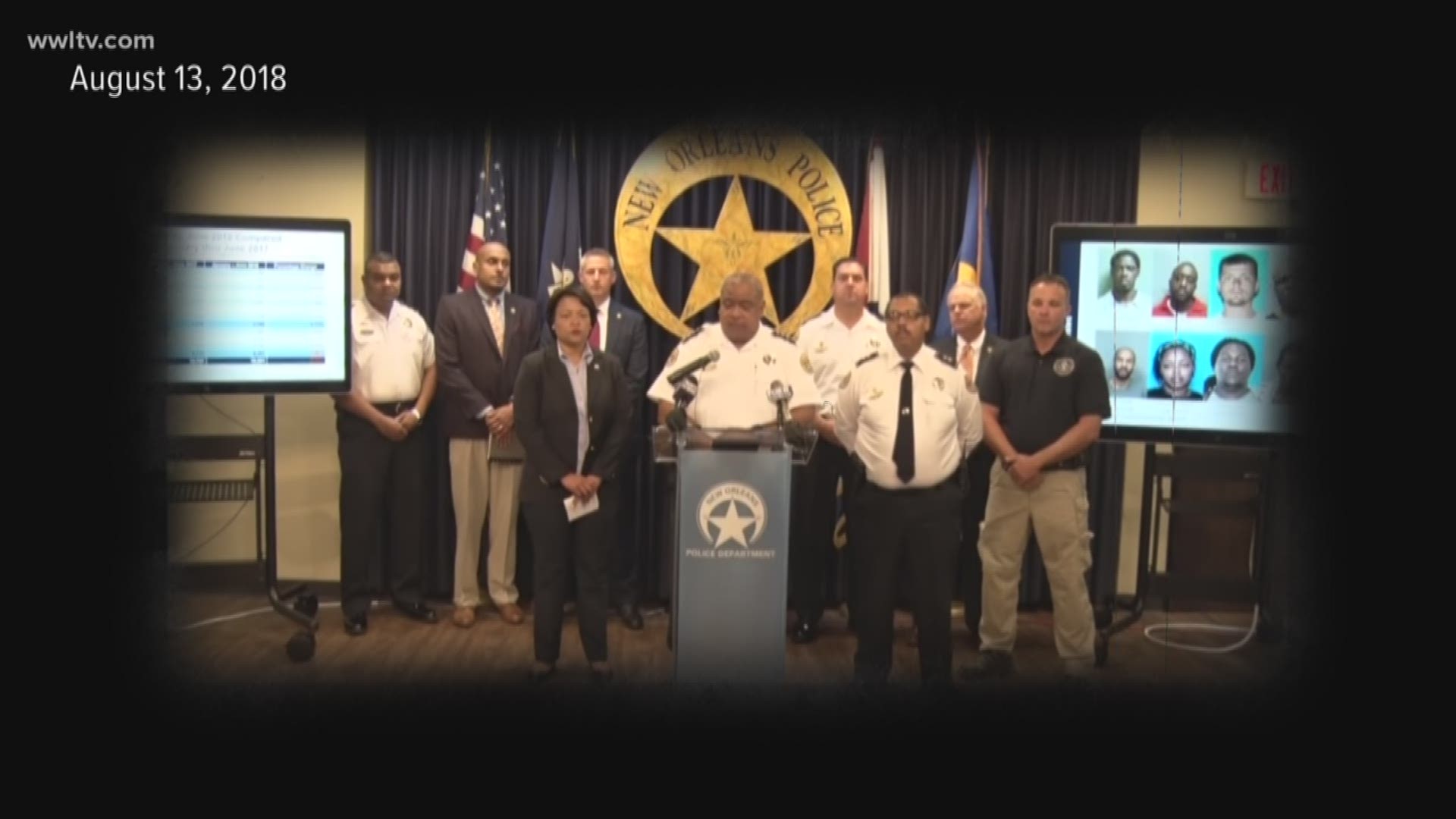

NEW ORLEANS -- When New Orleans Police Chief Michael Harrison announced the city's biggest drug sweep in years, Mayor LaToya Cantrell stood by his side to praise the risky undercover operation, dubbed “Summer Heat.”

Highlighting the connection between drugs and violence, Cantrell vowed to continue the crackdown.

“We are not going to let up until we ensure that they are off the streets of New Orleans,” she said at the Aug. 13 press conference.

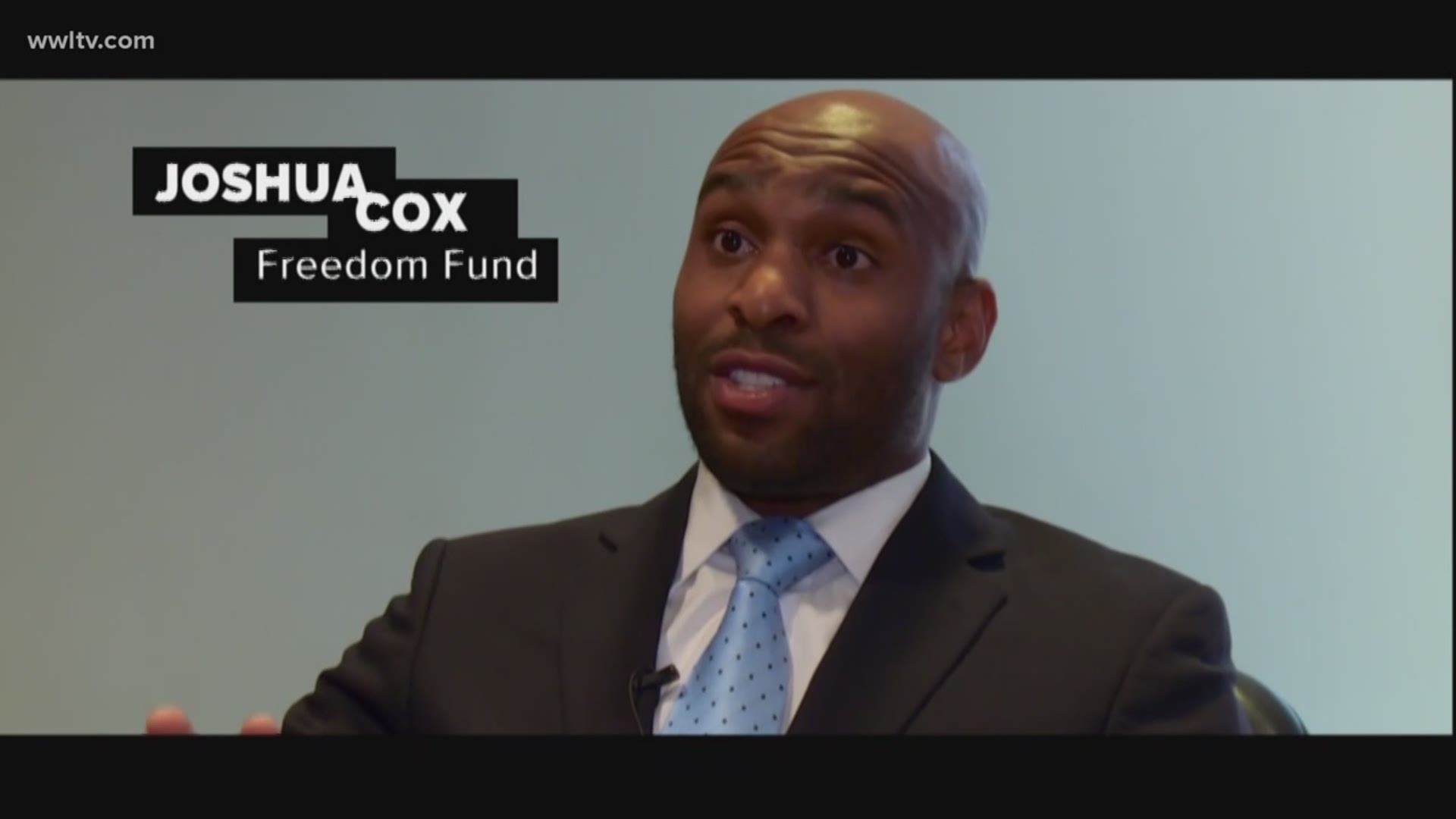

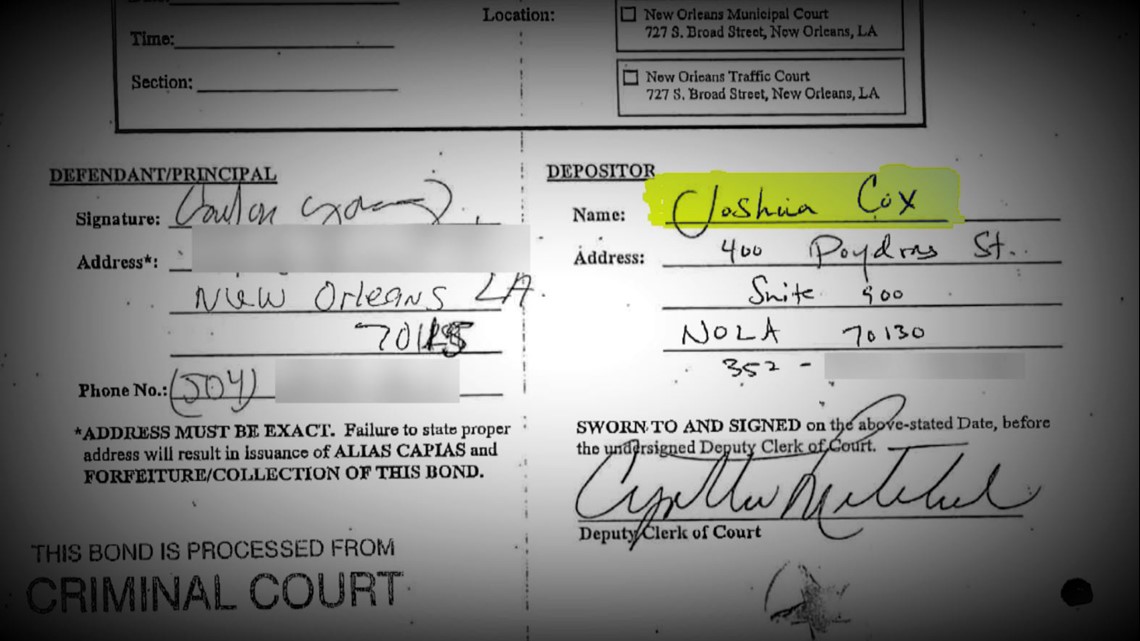

But shortly after the police rounded up 71 alleged drug dealers, another top official working for the mayor put his own stamp on Operation Summer Heat. Joshua Cox, Cantrell's director of strategic initiatives, helped bail out seven of the Summer Heat drug suspects, according to records obtained exclusively by WWL-TV.

Cox is the founder of the Freedom Fund, an organization that raises money to post bail for arrested suspects. Documents show the fund has been used to bail out about 200 suspects, paying more than $200,000 from a revolving fund financed by donors and activists.

Among the 200 suspects bailed out by the fund: seven alleged street-corner dealers arrested in Summer Heat.

The NOPD’s two largest police associations were taken aback by WWL-TV’s findings.

“They're going to put all that time and energy and effort and risk their lives to arrest persons that are serious threats, and then the mayor's office is somehow involved in their release?” asked Eric Hessler, attorney for the Police Association of New Orleans. “I don't understand what I'm looking at and can't comprehend why somebody would do that…It's kind of contradictory to common sense and public safety.”

Donovan Livaccari, spokesman for the Fraternal Order of Police said, “I think the message being sent to officers is a very strange message. I think it's a very strange message to the people who live in this city.”

Previous “Bail Out” stories by WWL-TV revealed that among the suspects helped by the Freedom Fund was a third-degree rape suspect was personally freed by Cox after he posted a $5,000 cash bail from the fund.

“You almost have to wonder if there’s a conflict of interest,” Hessler said.

Cantrell’s press secretary LaTonya Norton said the mayor sees no conflict in Cox’s involvement with the fund.

“Mayor Cantrell has complete faith in Mr. Cox, and no objection to the work he does independently with the Freedom Fund on his own time. The Mayor is not aware of any impropriety, and we believe there is no conflict with his work as part of the administration,” Norton wrote in a statement.

Cox incorporated the Freedom Fund one year before being hired at City Hall. The mayor's office would not allow Cox to comment, but other Fund organizers say he stays involved strictly as a volunteer in his free time.

More importantly, the fund organizers believe that what Cox launched is a long-overdue reform that helps keep people from doing unnecessary time behind bars. The private fund replicates other “angel” funds that have popped up in cities across the country amid a criminal justice reform push that tries to address the disproportionate number of poor people in jail.

“The existing system is actually locking up people who are not a risk to public safety simply for being poor, because they just don't have the cash to bond out,” said Jennifer Medberry, a co-founder. “That is actually very destabilizing.”

The fund started when a group of business entrepreneur, including Cox and Medberry, looked at the success of community bail funds elsewhere. Medberry says the Freedom Fund is developing its own solid track record, with 92 percent of defendants released though the fund making their court appearances and avoiding fresh troubles with the law. Donors can give as little as ten dollars a month, Medberry said. It's a revolving fund, meaning that once defendants complete their cases in court, the bail is returned, and the money goes back into the pool to bail out others.

“We identified money bail as one of the real risks to public safety and, by the way, a major taxpayer waste (due to unnecessary incarceration),” said Chris Laibe, another organizer.

Bail reforms, including the Freedom Fund, have quietly brought the New Orleans jail population to modern-day lows of just over 1,200 inmates.

Cantrell’s views on criminal justice have long been aligned with those of the Freedom Fund organizers. She campaigned for mayor on reforming the system, and recently wrote an opinion column with Council President Jason Williams voicing misgivings about how many people remain behind bars simply because they can’t afford bail.

“We all want a safe city, but financial bail does not make us safer. Unnecessary detention does not make us safer,” Cantrell and Williams wrote. “And our community pays the cost.”

Organizers say the fund only helps suspects with local ties whose bail has been set at $5,000 or less. With other sweeping bail-reform policies taking root at Tulane and Broad, most drug defendants now fall under that amount, including the Summer Heat suspects.

Like Carlson Young. Accused of selling crack to an undercover officer, Young's bail was set at $2,500 After he spent two weeks in jail, the public defender's office filed a motion for bail reduction, pointing out that Young has a job and community ties. A judge dropped the bail to $150. Records show that Cox paid the money, and Young was released.

A close look at Young’s criminal history shows that he has seven prior felony convictions – five of them felonies – and four separate stretches in prison. His most recent convictions include distribution of cocaine in 2013 and possession of heroin in 2009.

Medberry wouldn’t address the rap sheet of Young or other Summer Heat suspects, but defended the fund’s mission to help any local defendant locked up on relatively low bail. She said referrals on which defendants to help come from the Orleans Public Defender’s Office.

“Regardless of their charge, the judge has determined, based on the risk assessment that looks at criminal history, that that individual can safely return to the community,” Medberry said.

WWL-TV legal analyst Chick Foret, who has worked as a prosecutor and defense attorney, reviewed our findings.

“It looks like this was a well-intentioned program. Let's put together money so we can fund and get folks out of jail to they don't needlessly spend time in jail,” Foret said.

But Foret said he also sees risks, especially when the mayor's assistant is involved.

“There seems to be a conflict of interest in the city’s position,” he said. “You can't have this do-good theoretical concept and make it fit where you have dope dealers who have criminal convictions and are charged with serious crimes.”

Some of the biggest questions about Cox’s dual roles are coming from police officers, who also answer to the mayor. They hear Cantrell say that public safety is her top priority, but they see freshly arrested suspects being freed by Cox and his organization.

“Not only do we have a revolving door, but we're going to sit there with the oil can and make sure that it spins as quickly as possible?” Livaccari asked. “It seems problematic. Police officers are having a hard time understanding this.”