NEW ORLEANS — Dick Baumbach and Bill Borah called their 1981 book chronicling their fight against the infamous Vieux Carre Riverfront Expressway “The Second Battle of New Orleans.”

“Battle may be an understatement. It was a war,” Borah once said.

Fifty years ago today, the war ended and Borah, Baumbach and a dedicated group of French Quarter preservationists who fiercely fought the expressway could claim victory.

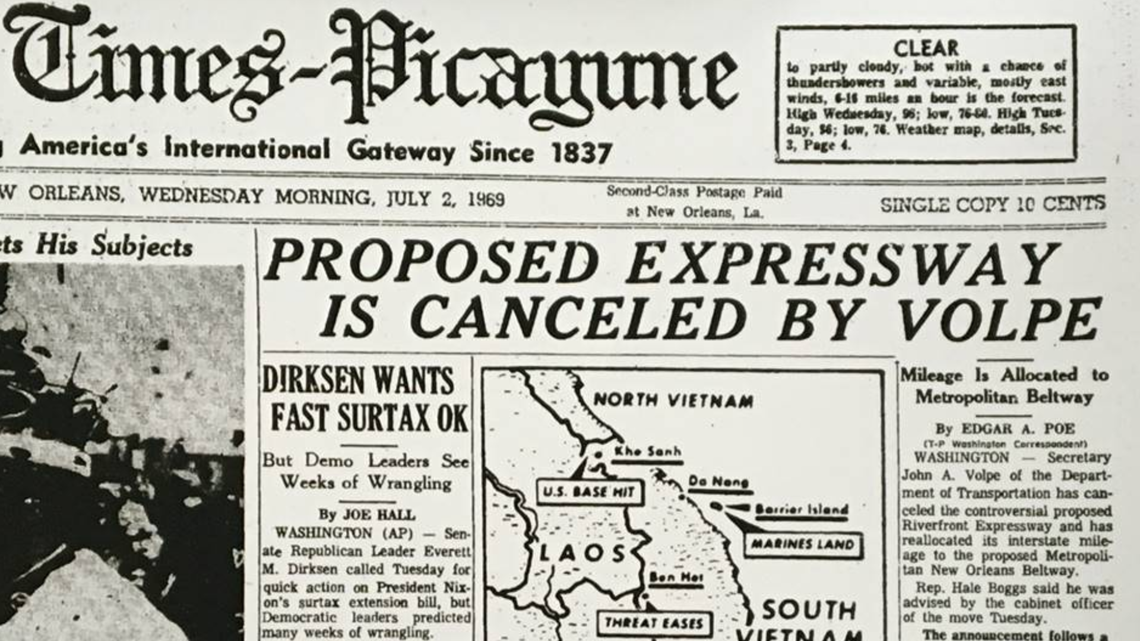

On July 1, 1969, federal Secretary of Transportation John Volpe threw up the white flag, cancelling the proposal for the elevated riverfront expressway which he admitted “would have seriously impaired the historic quality of New Orleans’ famed French Quarter.”

The decision ended a two decades-long fight waged by Baumbach, Borah and others who took on major forces in politics, business and the media, arguing that the proposed elevated, six-lane interstate highway would destroy the French Quarter's riverfront.

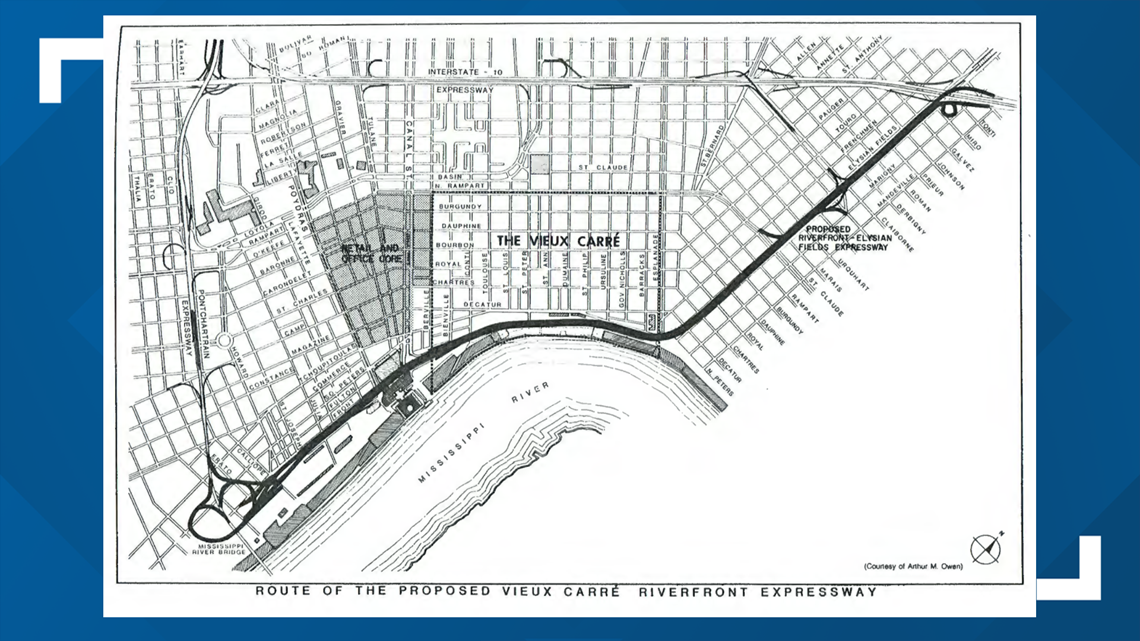

Plans called for the highway, 40-feet high and 108-feet wide, to travel from Elysian Fields Avenue along the riverfront in front of Jackson Square to Canal Street where it would descend into a tunnel near the Rivergate convention center and tie into the Greater New Orleans Bridge, now the Crescent City Connection. The Rivergate tunnel was built, even though the expressway ultimately wasn't.

“It (the expressway) would have changed the whole atmosphere or tout ensemble of the Quarter, that essence, that mystique, that unique culture that the French Quarter is,” Borah, who died in 2017, said in a 1995 WYES-TV interview.

"I think that it was miraculous that it was stopped," said preservation advocate and Louisiana Landmarks Society leader Sandra Stokes on Monday.

The highway plan, which was first developed by noted transportation planner Robert Moses in the 1940s, had widespread support from the mayor, city council and most in the business community. They felt the expressway was necessary to modernize New Orleans’ transportation grid and claimed that passing up the federal money earmarked for it would only accelerate the development of cities like Houston, Dallas and Atlanta. Locals were also excited by the prospect of the federal government picking up 90 percent of the project's cost.

“This was progress. They were doing these things all over America, had been doing them for some time. The thing about New Orleans is, as it does most things, it got into the business late,” Borah said in a 2016 presentation for the Louisiana Landmarks Society.

“Every government agency wanted this. Every major institution wanted this. The governor wanted it, the congressmen wanted it,” Borah said in 2016.

The highway also had support from two powerful voices in local media: The Times-Picayune and WWL-TV.

“How stupid can New Orleans be? That question takes on great relevance today after reading and hearing the news that this city might lose federal money available for our Riverfront Expressway,” wrote Phil Johnson in a Dec. 7, 1967 Channel 4 editorial. “(The city) might lose this money because of the blocking, stalling tactics of a small minority dedicated to the past.” Two years later, when a City Council vote approved the expressway, WWL lauded the move as a sign of progress. “The most talked about, the most controversial, the most praised, most damned, most surveyed and resurveyed issue in the history of New Orleans has finally been resolved,” Phil Johnson wrote in a Jan. 10, 1969 Channel 4 editorial. “They’re going to build a Riverfront Expressway. And hopefully, they’re going to build it soon.” In later years, Johnson would admit he and WWL were wrong for supporting the idea.

Despite strong support from those voices in the media, as well as New Orleans Mayor Vic Schiro, Rep. Hale Boggs, Sen. Russell Long, the Chamber of Commerce, Bureau of Governmental Research and most of the city’s business leaders, Borah credited the passion of French Quarter preservationists and other preservation leaders with generating opposition that eventually killed the idea.

“It was a war because the preservation community…in the French Quarter had fought to protect this area since the 1920s and here comes this highway that’s just going to devastate it and they’re fiercely fighting it and gradually people in other parts of the city joined them,” Borah said.

Borah, a New Orleans native, was fresh out of Tulane University law school when he and Baumbach, a fellow young lawyer, joined the fight against the project.

He admitted that he entered the fray almost by accident. He was ready to move to London to continue his schooling, when his father, Judge Wayne Borah, became ill. The younger Borah returned home and found a new calling and a willing partner in Baumbach.

“I remember we sat in Café Du Monde one particular morning and we both looked at each other and said have we got anything more important to do with our lives than to fight this highway? And we said no and we just devoted our lives to try to stop that highway,” Borah said in an oral history interview with the Historic New Orleans Collection.

The two young attorneys joined a fight that Borah was always quick to point out had really been brewing for decades, led by preservationists Martha Robinson, Mary and Jacob Morrison, Harnett Kane and others.

The fight gained ammunition when influential philanthropist Edgar Stern recruited Borah and Baumbach to lead the opposition and funded their efforts through his Stern Family Fund to learn about urban planning and travel to other cities where successful fights had been waged against highway proposals. The television station Stern founded and owned at the time, WDSU, also lent its voice to the opposition through broadcast editorials. The TV station was joined in its opposition by the alternative newspaper The Vieux Carre Courier, and The Clarion Herald, the newspaper of the Archdiocese of New Orleans. The opponents also earned the support of then-Archbishop Philip Hannan, who was new to town but had influential contacts in Washington, D.C. where he had previously served.

“This was an emotional issue. This was a fiery issue. This is an issue that split families, that split businesses, that split law firms. People didn’t talk to each other, not 10, 15 years,” Borah told WYES-TV in 1995.

Initially, Borah said the fight against the highway started small. “We started doing flyers. Every weekend we would do flyers of different kinds and we’d saturate individual neighborhoods with them,” Borah explained. He laughed that the opponents were always sure to put one of the flyers on the front door of Times-Picayune editor George Healy, a fierce proponent of the plan.

A more substantive campaign was launched during Mardi Gras 1967, with anti-Expressway banners hung from French Quarter balconies to attract the attention of national reporters in town to cover the celebration. “The decision was made to make this a national issue because it was becoming increasingly apparent that in New Orleans or Louisiana, we didn’t have a chance at stopping this thing. The City Council had come out in support. Mayor (Victor) Schiro supported it, the governor, different members of the Legislature,” Borah explained in the Louisiana Landmarks Society presentation.

“The thesis being that the Vieux Carre and Jackson Square, these were national historic landmarks, they belonged to the people of America as well as to the citizens of New Orleans,” Borah said in 2016. The effort landed the opposition scores of national news stories about their fight.

During a different holiday, preservationist leader Martha Robinson, who Borah lovingly called “The Senator” for her tenacity and political connections, notably mailed Christmas cards to her well-heeled list of contacts, with a view of Jackson Square blocked by a drawing of the expressway and the message “Merry Christmas from New Orleans. Stop the highway,” Borah said.

Separate battles were waged in court, but to most it still seemed like the highway was a done deal. Finally, on July 1, 1969, the news came that Volpe, who was President Richard Nixon’s new Secretary of Transportation, had decided to kill the proposed expressway.

“I turned to Dick Baumbach, and said, ‘Would you believe it? I just got a telephone call and they say the expressway has been canceled by John Volpe.’ Both of us said it at the same time. ‘We’ll believe it when we see it in the Times-Picayune.’ And the next day was the headline: Highway Defeated,” Borah said. “I can’t tell you the joy. Preservationists had been battling this thing for years, some of them, like Martha Robinson, going all the way back to the early 1950s. It was unbelievable. It was the first segment of the interstate highway system ever canceled in this country for environmental reasons. The first one, and after that there were others.”

WDSU-TV, which was one of the strongest voices against the expressway, said in a July 2, 1969 editorial that the decision to kill the project, while a welcome one, left unanswered questions about downtown traffic flow.

"The decision should bring neither bitterness from supporters of the expressway nor gloating from opponents. For now is the time for all elements who participated in the controversy to join together and seek reasonable - and workable - solutions to the downtown traffic solution.... The community can make a fresh start on overall transportation planning," wrote news director Ed Planer, who wrote dozens of WDSU editorials throughout the 1960s opposing the expressway, along with former news director John Corporon.

Though the Vieux Carre Riverfront Expressway had been defeated, a portion of the plan which called for an elevated expressway along North Claiborne Avenue had already been set in motion, tearing apart historically African-American neighborhoods by building a highway there. It wasn’t that Claiborne was pursued as an alternative to the Vieux Carre, Borah always pointed out. Instead, while the Riverfront Expressway leg of the plan was defeated, the Claiborne Avenue expressway was allowed to move forward, destroying oak trees that lined the avenue and, many would say, harming the urban fabric of the nearby neighborhood.

In 1981, Borah and Baumbach published their book about the Riverfront Expressway fight. It is set to be re-released this year, with a new foreword from journalist and author Jed Horne, who worked with Borah on the reissue before his death.

"To me the amazing thing about the whole fight is that it demonstrates how completely wrong the establishment can be," Horne said. "The lesson from Borah and Baumbach and their allies, who were numerous, is that you can turn back the Titanic. You can turn that energy aside and get something sensible done."

Baumbach died in 1993. Shortly before Borah’s death in 2017, he spoke at a ceremony where the Vieux Carre Property Owners, Residents and Associates group unveiled a plaque along the riverfront commemorating the Riverfront Expressway victory. In the years since that fight, Borah had become known as a fierce preservation attorney, taking on many other battles. The successful fight against the expressway was seen as a critical first step.

“We all know that eternal vigilance is the price we must all pay for democracy. We have also learned that it is also the price we must pay if we desire to protect and preserve ‘the quaint and distinctive character’ of this city that we all love,” Borah said. “Make no mistake about it, the defeat of the Riverfront Expressway was an extraordinary accomplishment. And we all made it happen.”